In our series on gardening in style, we pay tribute to Valerie Finnis’ portraits of the great gardeners of her day. We’re asking some of our favourite garden people, “What do you wear to garden, and why?” Our latest contributor is award-winning garden designer, writer and broadcaster James Alexander-Sinclair:

Gardening is supposed to be above fashion: it is about connection with the earth and extreme practicality rather than kowtowing to fashion. In times gone by there were standards – all the gardeners in suits and waistcoats clustered around a stentorian, fob-watched head gardener.

Nowadays we are not that bothered with style: the days of Vita in her high boots or Nancy’s sombrero are mostly gone gone. Monty Don has a seemingly inexhaustible supply of thick blue cotton suits that make him look like a 1930s farm-worker resting from a hard morning sheaf-hoicking.

Alan Titchmarsh is quite the dandy and has a very splendid Sherlock Holmes style caped Ulster coat for visiting flower shows on cold days. Ann-Marie Powell has a vast collection of floral dresses (all with matching underwear). But, apart from high days and Chelsea Flower Show we seldom have the chance to dress up – in my book this is a pity as I like the chance to wear a suit and have a penchant for a bit of bespoke.

A brief top to tail tour of the well dressed gardener

HATS

In times gone by everybody wore a hat: you could tell the mettle of a chap from his hat. Women would not go out without cloche or bonnet, men could not be seen sans flat cap or homburg. Everybody had something which, not only kept the head warm, but also allowed scope for style and meant (if male) you always had something to doff when the opportunity arose.

Nowadays a hat is seen more as an affectation than a necessity.

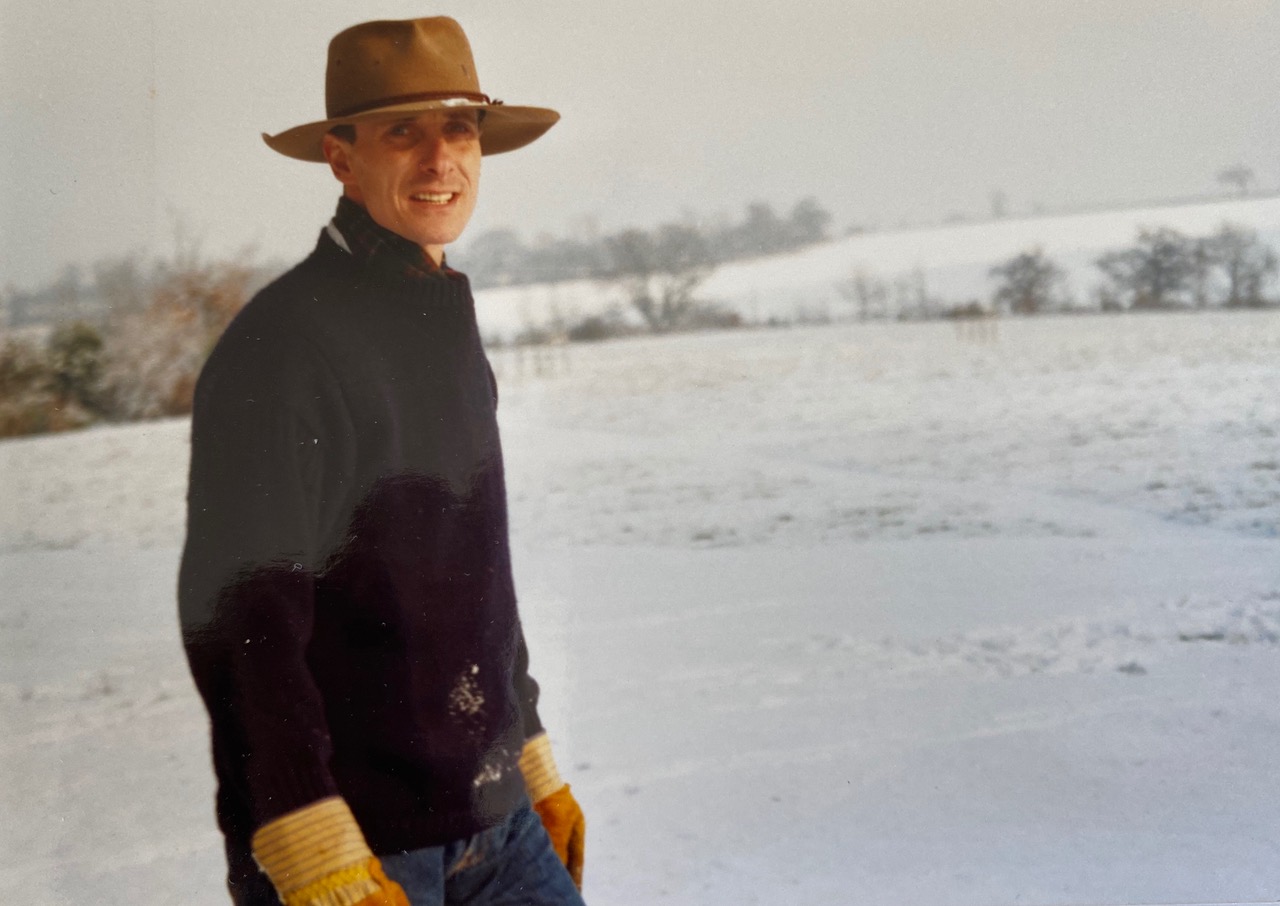

I long ago discovered the advantages of a large hat while gardening. So much so that it became a trademark for a while which was fun. I have no idea how many times people have said “I didn’t recognise you without the hat!” which is a nice entree into a conversation. The hat (an Australian Akubra) was made from finest rabbit fur and at peak chapeau I owned six of them although I am now down to two – one got eaten by a dog, one ended up on a fireworks night Guy and I annoyingly left one on the luggage rack of a train bound for Glasgow. The hat sheltered from the rain, protected from the sun and, if really hot, can be filled with water and slammed on the head as cooling shower.

I stopped wearing it a few years ago when I started having to wear glasses, as I was told by my wife, who has excellent taste in these things, that the combination was not doing me any favours. so the hat went. It had been part of my life for over twenty years so it probably needed a rest. I now only wear that hat in extreme weather and instead have a good grey tweed baker’s cap, a battered straw number, a selection of bobble hats (knitted by my sister), a Glengarry, a repulsive fleecy thing that I bought from a garage and lives in the boot of my car, and a Basque beret which I think stylish and others consider ridiculous.

JACKETS

I suppose that it does not really matter what one wears for gardening provided it is warm, sturdy and, most importantly, comfortable. My father-in-law, for example had an old waxed jacket that, frankly, was more hole than jacket. This rather defeats the purpose of a waterproof jacket but it makes him happy. The most waterproof garment I possess is a New York Fireman’s coat: it is heavy, (presumably) flameproof and fastened with impressive shackles. Unfortunately it is more suited for wrangling hoses in Brooklyn than weeding so I only really wear it for unblocking flood drains.

The invention of fleeces and Goretex have transformed gardening garb at the expense of style, but I suppose it means that we can stay out longer without our tweeds becoming so sodden that it is like carrying a drunk llama on your back.

TROUSERINGS

I once interviewed a gardener who was pruning roses while wearing nothing but a salmon pink thong. This experience convinced me that gardening is always better and safer if one is wearing sensible trousers.

I have laid a terrace while wearing tweed plus fours and put up trellis while clad in a kilt (possibly the least sensible garb for landscaping, especially when up a ladder on a breezy day). I have swaggered, when much younger and in proud possession of a torso that was less like an old mattress, around topless wearing only smallish shorts. For a while I had a great pair of Women’s Land Army corduroy breeches which I acquired somewhere and gave lots of space for bending and flexing (although inconveniently devoid of fly buttons). I used to ransack the recycling for old pairs of my mother-in-law’s trousers (an activity that, now I write it down, sounds much more perverse than it actually is) which produced many useful garments.

SOCKS

Socks are very important: so much so that I think that they are the best present anybody can give. This view does not necessarily conform with the conventional which tends to think that socks are last minute panic presents for male relatives. On the surface they may be dull and practical but, if you stop and think a moment, they are so much more. If you ever have need of a short cut to my heart then forget jewels beyond compare, leave your dancing girls (trained in the 396 ways of love) at home and bring me socks.

I have a lot of them: everyday striped numbers (originally purchased as they were instantly recognisable and could not be easily snaffled by my sons). Cashmere socks which are useless for wearing with boots as the constant friction makes holes very quickly. I have inherited some fine hand knitted shooting socks that belonged to my grandfather and even a pair of slightly pervy silk evening socks that I have never worn. Alpaca socks are the best, which are the sort of things that snort at cold weather – they might have trouble in Yakutsk, Siberia (where it averages out at a bracing -40°C) – but are more than adequate for the home counties, especially when teamed with one of the greatest inventions of the modern age: the neoprene lined wellington boot. (If you feel the urge for an excellent sock may I point you to the Horatio’s Garden website? They have excellent Alpaca numbers and you not only get warm feet but the chance to support one of the world’s finest charities.)

GLOVES

The glove debate agitates some people: on the one hand there are those who feel a pair of gloves is sensible as it keeps the hands clean and undamaged. The other side argues that if you cannot actually feel the soil then you are missing an essential element of gardening – I watched Monty Don on television pulling out brambles with his bare hands which struck me as taking it a tiddly bit too far.

I have sympathy with both viewpoints.

When fossicking about on a summer’s day then, of course, it is wonderful to feel the soil running through your fingers. But if it is freezing cold and you are laying into a thorny hedge then only the most deranged gardeners would do so without some protection – a bit like those football fans who insist standing shirtless on the terraces in February.

I have a number of pairs of gloves for garden use: ranging from assorted builders merchant standards to a terribly luxurious thermal lined pair made of soft leather. The very best pair that I have ever owned was given me by my brother who found them in a truckstop somewhere near Fruitland, Idaho. They were the colour of George Hamilton’s suntan and made from tough suede. Sadly, I only have one left as the right hand glove accidentally ended up in the compost heap and, by the time I found it after about a year’s mouldering, a mouse has removed most of one finger as nesting material. This is not that unusual a fate for a gardening glove…

—