Rosie Vizor, Garden Museum Archivist

With the Museum being closed to visitors, now is a good opportunity to delve into the boxes of some of the lesser known archives we hold. This week, I have been cataloguing the archive of Victorian Head Gardener, Matthew Balls (1817-1905). Since our collecting focus is contemporary and 20th century garden design, I was excited to see this older material, especially because archives of Victorian Head Gardeners are rare.

When we think of Victorian gardens, we picture colourful carpet bedding, great glasshouses, elaborate fountains and statues, exotic plants and trees in arboretums. We associate them with the famous landscape designers and plant hunters of the time, but garden historian Toby Musgrave argues that Head Gardeners are the ‘Forgotten Heroes of Horticulture’. [1] It was they who had to cultivate plants on home soil and the great majority of country house gardens were designed by the Head Gardener, not by a travelling professional designer.

The Head Gardener has been an elusive character for many years; his name may appear on a list of the owners’ wage payments, or attached to a variety he first cultivated, but little of his personal life is recorded, especially not by himself. That’s what makes the Matthew Balls Archive so precious; donated in 2011 by Anthony Paice, Balls’ great-great grandson, it arrived with an accompanying family history tracing back to 1575.

Matthew Balls was born on 23 March 1817 at Gaynes Hall, West Perry, Cambridgeshire, to Henry and Ann Balls, who were both servants. Henry was a gardener, as was Matthew’s grandfather. Matthew married Elizabeth Flint on 30 July 1842 in Godmanchester. They subsequently moved to Hertfordshire, where he was appointed Head Gardener at Stagenhoe Park by the time he was 30, but what happened in between? How did he rise to such an illustrious post, leading a team of up to 20 gardeners?

Rising Through the Ranks

If you wanted to be a gardener, like Matthew Balls, you had to commit to an apprenticeship of up to 15 years. Only the best and most committed uneducated boys were taken on, learning from older gardeners. Matthew probably would have started off as a gardener’s boy at a large establishment, aged 12-14. His jobs would have included washing flowerpots (huge numbers were required for carpet bedding), sweeping paths, and carrying coal for boilers heating glasshouses, which would need constant stoking. Gardening boys worked ten hour days, six days a week, while studying the latest horticultural publications in the evening. They would pay the Head Gardener for their training, and he would issue fines for rule-breakers.

After a year or so, Matthew might have started work in the kitchen garden or glass house, progressing to an ‘improver’ by age 17 or 18. Improvers were ‘upwardly mobile young gardeners’ who learnt while practising. [2] Improvers lived beside ‘journeymen’ (gardeners in their 20s who travelled to develop their skills further) in a bothy, which were sometimes set into the walls of walled gardens. They were expected to remain single. After a long, hard day’s work, came evening study – everything from botany, etymology, plant physiology and trigonometry, to plant breeding and the cultivation of flowers, fruit and vegetables, some of which had never been grown in the UK before.

Few 12-year-olds would rise through the ranks to Head Gardener, but ambitious gardeners might start advertising their availability for Head Gardener jobs by the time they were 30, as Matthew did.

Head Gardener at Stagenhoe Park

Henry Rogers appointed Matthew as Head Gardener at Stagenhoe Park in 1846/7, having purchased the estate in 1841. Next door is St Paul’s Walden, with its famous formal garden of the 18th century. Records of Stagenhoe manor date back to the Norman Conquest (it appears in the Domesday Book) but the mansion Matthew worked at was originally erected around 1650-1660, then burned down in 1737, and was rebuilt in the Palladian style in 1740.

As Head Gardener, Matthew would have been responsible for the upkeep and development of the parkland landscape. According to his descendants, Matthew had a team of 20 gardeners under his direction. We can get a sense of what he created at Stagenhoe from the photographs and plans in the archive, which is held at the Garden Museum.

This engraving shows the house with an adjacent conservatory. During Rogers’ ownership, a new entrance and carriageways were constructed, as well as a large ornamental lake with small islands, a fountain, waterfall and stew ponds for fish. [3] Soil excavated from the lake was used to build up a terrace in front of the house.

There was also a terrace to the side of the house, off the conservatory, with a broad-stepped path flanking the walled garden. The walled garden was in existence before the 19th century but its walls were rebuilt with Italianate piers by Rogers. The path led down to woodland, where there was a fountain, through to St Paul’s Walden Church, which the Rogers family attended.

The entrance to the walled garden was through large double gates, known as the Stag Gates.

On the north side were two servants’ cottages, rebuilt during Rogers’ time, which opened onto the walled garden. By 1851, Matthew was living with his wife and four children (Matthew Henry, Elizabeth Mary, James and Sarah Ann) in one half of the gardener’s lodge. The other half was occupied by William Exton, the butler, and his family.

This 1881 map shows that within the walled garden there was a pond with a bridge over the centre. The area marked ‘20’ on the map shows the position of a Cedar of Lebanon tree, photographed by Matthew. The cross-hatched sections indicate glasshouses.

The glasshouses would have been used to grow thousands of colourful plants that would be ready to flower at the same time for fashionable carpet bedding schemes, and floral arrangements in the house. Glasshouses enabled gardeners to cultivate the influx of exotic plants from around the world brought back by plant-hunters, whose expeditions were often funded by competitive garden-owners and commercial nurseries. There was a constant strive for novelty from garden-owners, who also sought new foods to distinguish them from the masses, supplied by the kitchen garden year-round. The reputation and fame of the great houses rested on the Head Gardeners’ skills; as such they were highly respected figures, expected to enter flower shows and write for gardening magazines. There was a thriving network of Head Gardeners, over 4000 in 1914, who swapped plants and shared knowledge and professional standards.

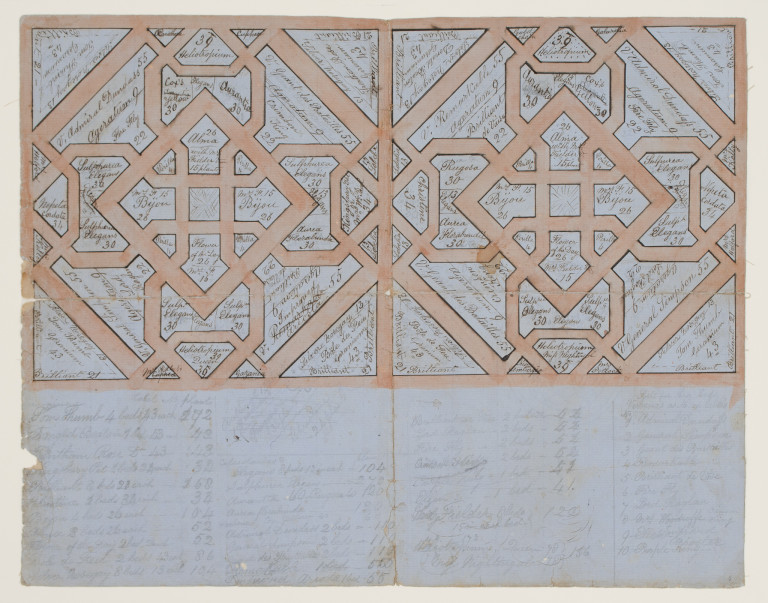

What is very unusual is that these designs by Matthew survive. There is a working drawing in the archive showing Matthew’s scheme for a parterre on one of the terraces, which was possibly located on the front terrace, flanking the central axis path. The intricate design is geometric and symmetrical, characteristic of the period, featuring gravel paths separating flower beds. This scheme is for summer bedding plants, with quantities calculated and pin pricks to show where to plant them. Matthew would have conveyed this plan to his team of gardeners, who would have worked in the hothouses to prepare the plants for summer flowering, when they would be at their best for Rogers to show off to visitors. The plan includes lists of geraniums, calceolarias, and verbenas.

As we can see in Matthew’s plant list, many plants were named after the Head Gardeners, their wives, and possibly their employers or notable figures. For example, Donald Beaton (a ‘star’ Head Gardener in Scotland), Mrs Woodroffe, Lord Raglan, and Mrs Nightingale (possibly Florence).

We are lucky that the archive contains a photograph of another of Matthew’s executed designs, together with the watercolour plan. The numbers on each bed correspond to the plants used; the list for this design didn’t survive, but we can get a sense of the intended colour palette. This plan may have been used to present to his employer, or to visualise how the colours would work alongside each other. We can see that this parterre was situated on the terrace next to the walled garden, with Yuccas positioned in each corner. This style of garden is very far from our fashions today, but the drawings highlight the level of skill and labour involved in carpet bedding.

Leaving Stagenhoe

In 1869 James Sinclair, 14th Earl of Caithness, bought Stagenhoe Park, and shortly after Matthew left his position as Head Gardener. Most likely he resigned, as the Earl brought his own gardener from Scotland. The Balls family moved to Cangles, Chaulden Lane, Hemel Hempstead, where Matthew was still working as a gardener in 1871. By 1877 they had moved to Isleworth, and by 1881 Matthew was working as the Cemetery Superintendent for the new cemetery and living in a Lodge at the entrance. Henry Rogers’ son employed Matthew’s children as servants in his new residence in London. Matthew died on 5th November 1905, aged 88, leaving £1352 (no mean sum) to his daughters.

The Victorian Head Gardener

Matthew’s archive adds to the hidden history of Victorian Head Gardeners, people who, despite being among the servant class, were well-respected at the time, but whose lives have been largely overshadowed in the historical record by their clients. Matthew’s archive leaves a trace of his life recorded by himself, rather than just a name on his employers’ wage books. Was it Matthew’s pride in his designs and his ability to execute such a choreography of colours, that meant he preserved these working drawings, which so rarely survive? If so, he should be proud; combining hard work with an exceptional range of skills, the Victorian Head Gardener’s story deserves to be remembered.

—