In her prizewinning biography, Beth Chatto: A life with plants, Dr Catherine Horwood tells the story of Beth’s relationship with Cedric Morris through her diaries and letters, which she had exclusive access to before Beth’s family deposited the archive at the Garden Museum. This week, we’ve been looking through the archive to learn more about this great gardening friendship. Here, Archivist Rosie Vizor shares some of the extracts and photographs we found.

In Beth’s biography, Catherine Horwood explains that if it wasn’t for her husband Andrew’s friend Nigel Scott, they might never have met Cedric Morris. They had all heard of his notable garden at Benton End, near Hadleigh in Suffolk, and rumours of the bohemian set who gathered there, but none of them had ever been introduced. Catherine explains:

‘when Nigel casually said one Sunday at Braiswick in the mid-1950s, “Why don’t we go over and see Cedric Morris?’[…] Beth and to a lesser extent Andrew, were taken aback by the suggestion. […] It was not “the done thing – just to go and invite yourself to see the gardens”. (Horwood, 56)

The charismatic and impulsive plant enthusiast Nigel had no such qualms, promptly called Benton End, and got them all an invitation to tea. Driving down the winding Suffolk lanes to Benton End, none of them suspected that this trip would change their lives.

In her article for the iconic first issue of Hortus, Beth reminisced about the momentous occasion of visiting Benton End for the first time:

‘We […] entered a large barn of a room, the like of which we had never seen before. Pale pink-washed walls rising high above us were hung with dramatic paintings of birds, landscapes, flowers and vegetables […]. Bunches of drying herbs and ropes of garlic hung from hooks on a door, while shelves were crammed with coloured glass, vases, jugs, plates with mottoes – a curious hotch-potch, remnants from travels in years past.’ (Chatto, Hortus, 14)

She goes on to describe how from the long table, six heads belonging to more of Cedric’s eager visitors turned to face the new arrivals. At the far end, the lean figure of Sir Cedric Morris, famous artist and gardener, rose to greet them, informal and courteous, ‘elegant in crumpled corduroys’ and a soft silk scarf. His face ‘creased into a mischievous grin’, three more broken mugs were found, and Cedric poured tea.

The real fun came when they entered the garden. At this point in her life, Beth considered herself a novice plantswoman, especially compared to her expert husband: ‘walking behind the three men, pricking up my ears (I recognized perhaps one Latin name in ten) I felt like a child in a sweet shop, wanting everything I saw.’ (Chatto, Hortus, 15)

It wasn’t a conventional garden. In a letter thanking Beth for helping with his dissertation on Benton End (both now in the archive), David Oelman captures the spirit of the place:

‘You have given me a totally different view of the garden at Benton End, most people saw it as a mass of plants but you confirmed my suspicion that it was more than that and that the artist’s eye created a palette that was his own’.

Beth agreed with this description of the garden as Cedric’s artistic creation:

‘Dotted here and there were pillars of old-fashioned roses and several huge clumps of sword-leafed Yucca gloriosa. The rest was a bewildering, mind-stretching, eye-widening canvas of colour, texture and shapes, created primarily with bulbous and herbaceous plants.’ (Chatto, Hortus, 15)

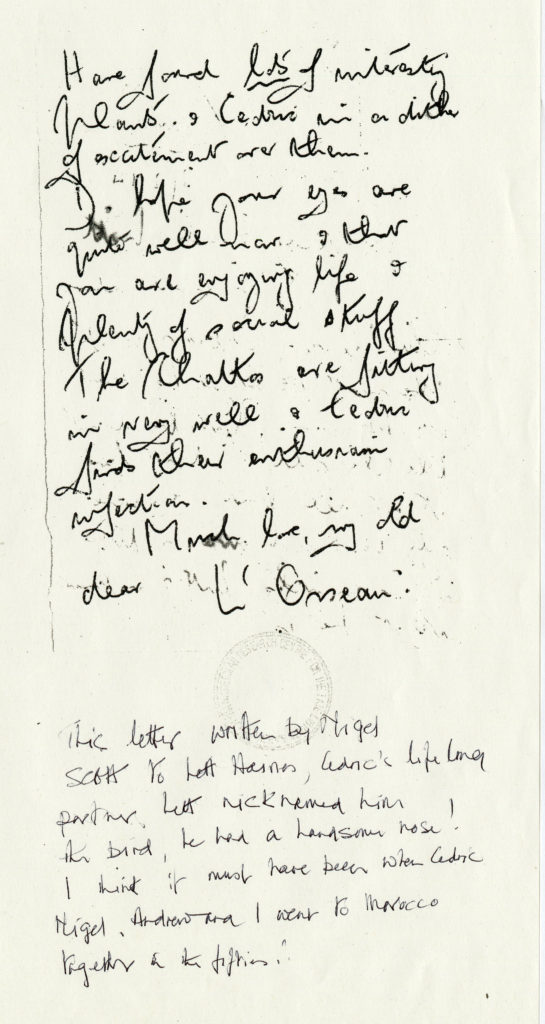

Beth, Andrew and Nigel’s first visit to Benton End sparked life-long relationships for each of them. The Chattos would visit their new friend regularly, sharing knowledge and cuttings. Nigel and Cedric became lovers and worked together on the garden. The four of them would go on holidays and outings together. Nigel, affectionately called ‘the bird’ with a ‘handsome nose’ by Cedric’s partner Arthur Lett-Haines (nicknamed Lett), sent him a postcard from Morocco, enthusing about the plants that he, Cedric and the Chattos had found on that trip.

As Catherine explains, for Beth, as the daughter of a policeman in rural Suffolk, Benton End was a world of ‘both daunting simplicity and frightening sophistication’ (Horwood, 56). Cedric and Lett’s Bohemian hospitality attracted the cream of London’s artistic and horticultural society, yet if the plumbing failed, no one was exempt from using the trench as a toilet (Horwood, 56). Beth was being quite daring by entering into this world but she met many of the great gardening experts of the time in Cedric’s garden.

It wasn’t just friends he gave her, but advice, inspiration and, crucially, cuttings. Beth writes that Cedric was ‘One of the two people who influenced me most’, along with her husband (Chatto, Observer). One evening, Cedric told Beth she’d never make a real garden unless she moved to a better site. The Beth Chatto Gardens and her nursery of Unusual Plants at Elmstead Market would not be where they are today if it wasn’t for Cedric’s decisive advice.

Beth tried to make the plant exchange a two-way enterprise but despaired that she was ‘rarely able to take something he did not already possess’, as she explains in a memoir in The Garden magazine, one of the many manuscripts and writings in the archive. However, one exchange in the archive stands out. The house at Benton End was cold in winter and Cedric would often disappear to warmer climes to paint and plant-hunt. On one such trip in 1956, his friend Basil Leng gave him a tiny narcissus he’d spotted on the roadside near Ribalden, in Spain. This ‘lovely little daffodil’ inevitably ended up in Beth’s garden too, where she grew hundreds of bulbs to sell. In a letter to Cedric, she asked to name it after him. On his 90th birthday, on 11th December 1979, Beth presented him with a bowl of Narcissus Minor Cedric Morris, already in flower before Christmas. Years later, Basil went back to the same verge but the road had been widened and the narcissi destroyed; it only survives in cultivation, thanks to Basil, Cedric and Beth.

Even in his eighties, Cedric gardened at dawn: in her diary for 21st May, Beth writes that ‘he is getting very old but gardens still. The walled garden is under control even tho’ weedy’.

Cedric died in 1982 at the ripe age of 93. An invitation in the archive from Glyn Morgan, a former pupil at the school, reveals the emotion Beth felt when returning to Benton End to celebrate the unveiling of a plaque:

‘I went, reluctantly at first, but […] we met many old friends. […] It was warming to see these people, but cold and sad inside to find only the husk of Benton End. But in the garden, reduced to overgrown trees and shrubs, with here and there brave cyclamen and tall colchicum, I collected seeds of Cedric’s special umbellifer standing tall and spare, like himself. I thanked him and drove sadly home.’

Cedric appointed his neighbor Jenny Robinson as his ‘plant executor’ and she entrusted many plants from his collection to Beth, which are still available at her nursery as part of his legacy, such as Papaver orientale ‘Cedric Morris’. In 1997, she wrote that ‘the highest proportion of plants in my present garden […] came from Cedric originally, as seeds, cuttings, scraps, or generous big clumps’ (Chatto, The Garden). We are very proud to be custodians of an archive which records one of the great gardening friendships.

The house was recently acquired by the Pinchbeck Charitable Trust, with whom the Garden Museum is working on a long-term plan to revive Benton End as a centre of art and horticulture. Read more about the project here.

Sources:

Beth Chatto, ‘Beth Chatto,’ The Observer (1988)

Beth Chatto, ‘Sir Cedric Morris, Artist Gardener,’ Hortus (Spring 1987): 14-20

Beth Chatto, Untitled typescript of article for The Garden (c. 1996-1997)

Catherine Horwood, Beth Chatto: A life with plants (London: Pimpernel Press, 2019)

All images are taken from the Beth Chatto Archive, © The Beth Chatto Estate. Please contact us in the event that you are the owner of the copyright or related rights in any of the material on this website.