by Jane Harrison, Project Archivist: Beth Chatto Archive

I’m lucky enough to be engaged in cataloguing the Beth Chatto papers thanks to a nine-month project grant by Archives Revealed, funded by The National Archives, The Pilgrim Trust and The Wolfson Foundation. The project aims to make the collection accessible to the public for the first time through cataloguing and digitisation, and use the information within it as the basis for a wide variety of outreach activities. The archive contains over two thousand documents and in the three weeks I’ve been working with the material I’ve only just scratched the surface.

Arranging and cataloguing an archive collection is a process in several stages: the first is to create a detailed list of all the documents, finding all the puzzle pieces and starting to work out how they might fit together. This might seem like a simple, rather tedious task, but it’s a chance to get an idea of the patterns of a person’s life, which in turn help in arranging their archive into an order as close to the original as possible. This is important as it’s not just the content of the documents themselves that will be of interest to future historians but how they relate to each other and what this can tell us about how a person lived their life.

We’re fortunate that Chatto was aware of the importance of her papers to history, agreeing to donate her collection and working with historian and biographer Dr Catherine Horwood, author of ‘Beth Chatto, a life with plants’, to prepare her archive for transfer to the museum. I’ve never worked with an archive so carefully curated, and I was nervous that the order in which Chatto left it might not reflect the actual pattern of her life and of the original order of documents. I shouldn’t have worried: many documents are kept in their original folders, and others have notes added to them by Chatto herself explaining their importance to her, which give a wonderful insight into both the collection and her life.

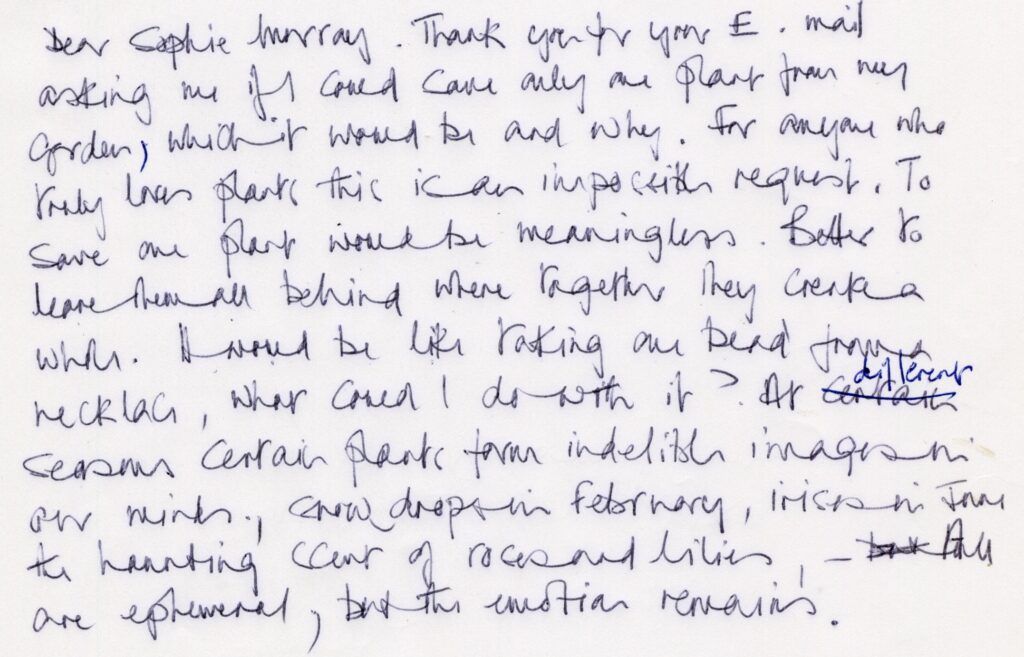

I’m only at the beginning of the project but I’ve already seen enough to realise what a rich resource the archive will be. There is already an accession list of much of the collection so I’ve started with the uncatalogued material, which includes Chatto’s correspondence with her publishers. As a Chelsea gold medallist and author of several influential gardening books she was in constant demand for interviews and articles on all aspects of gardening. Even in this professional capacity her personality comes through strongly; whether it’s her kindness in answering questions from garden design students and support for fellow garden writers, or the patience with which she answers questions for endless press articles (her favourite garden tool, a swoe – I had to look it up, what she might want for Christmas in 2002, a bird bath – ‘nothing too elaborate or fancy, preferably in wood’). But it is also clear that she wasn’t willing to compromise on her philosophy of planting: when asked for her favourite plant, she could not name one, ‘Every season brings its own treasures – How could I choose a favourite child’. Another article asked her what plant she would save from her garden if she could only have one; I found her reply really interesting:

‘For anyone who truly loves plants this is an impossible request. To save one plant would be meaningless. Better to leave them all behind where together they create a whole. It would be like taking one bead from a necklace. What could I do with it?’

This is exactly the same in an archive: while some individual pieces may stand out as particularly interesting, their value and interest decreases dramatically if they’re taken away from the whole, like a bead from a necklace. In fact, while there are umpteen ways an archive is not like a garden, there are pieces of Beth Chatto’s planting philosophy which fit rather well: the idea of looking for the right place for a plant, fitting it amongst those from similar circumstances, is similar to how I might go about placing a document which has gotten out of order. And, like a garden, an archive is a collection of things which have been taken from their natural habitat: just as it’s impossible to keep every document a person creates, so it is impractical to try to bring whole eco-systems into a garden. However, as Chatto discovered, it is possible to create something meaningful despite this by paying attention to the origin of the plants and their native habitat, or in archive terms, their provenance and original order. I’m planning on keeping this in mind throughout the project, and I hope that by the end the catalogue will be something Beth Chatto might have appreciated.

All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate.

Catherine Horwood’s biography of Beth Chatto, Beth Chatto: A life with plants (London: Pimpernel Press, 2019) is available at the Garden Museum Shop, ₤30.

You an find out more about the project to catalogue the Beth Chatto Archive in this blog post.