Can you name the Patron saint of gardening? Count to ten. The answer: St Fiacre.

If you’ve ever heard the name it’s likely to have been in a 19th-century French novel: a character in Flaubert will jump to his feet and ask a waiter to ‘get me a fiacre’. That’s a cab: from the 17th-century you hired a horse-drawn carriage from the Hotel de St Fiacre, and the name stuck. St Fiacre is also the patron saint of taxi drivers.

The original St Fiacre was Irish, born in County Kilkenny in the 7th-century. He was a hermit skilled in growing medicinal herbs, but who emigrated to France when too many disciples itched against his solitude. At Breuil, in the region of Brie, he built an oratory, and asked to make a garden. The Abbot permitted him as much land as he could trench around in one day. God granted Fiacre’s staff magic powers, so that its tip would topple trees and uproot bushes. Divine Groundforce. There he continued to grow medicinal herbs.

He was buried in the Cathedral at Meaux in 670 AD. His relics were supposed to cure haemorrhoids as once, it is said, he sat on a stone and it became soft. Haemorrhoids – called ‘St Fiacre’s figs’ – and not gardening explain the popularity of his cult in the Middle Ages.

That’s from Wikipedia, I admit. I had never heard of St Fiacre until a medieval statuette came up for sale at an auction house in Edinburgh. We received pledges of over £8,000 led by The Art Fund but as I sat bidding by the phone the price sailed by (‘ten thousand, eleven thousand’) like a bus that swooshes by your stop in the rain. St Fiacre is a rare saint to find.

Our application to the Art Fund required expert advice, which was volunteered by Paul Williamson, Keeper of Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics and Glass at the V&A. That’s a responsibility for one-sixth of the world’s biggest art Museum but Paul found time to share his expertise in such pieces. When we told him that we’d been outbid he said ‘But we have one. It’s better. And it’s not on display’. Thanks to the kindness of the V&A this carving will be displayed on long-term loan in the new galleries of the Museum

Alabaster is softer than marble, so quicker to carve, and therefore cheaper to buy; it is too soft for the exterior of a church, however, and would have been painted in vivid colours for votive display inside. From the 14th-century until the Reformation carvers at the alabaster quarries in the south of Derbyshire had a busy trade in exporting such pieces to the continent. ‘Our’ St Fiacre may have been intended for a church in France, where the cult was centred; or he may have been carved in Meaux itself, which also produced alabaster statuettes of this convenient size. The V&A’s piece was bought in Paris by Dr D. L. Hildburgh in 1926. The cult was also popular in the Low Countries and it is just possible – Emma House, our Curator wonders – that Tradescant may have glimpsed such a figure on his travels.

But we know that the robed figure is St Fiacre because of the spade he holds.

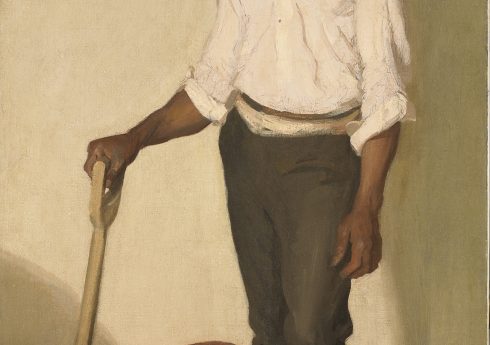

The iconography of gardening has changed little from John Tradescant to Alan Titchmarsh: compare the DeCritz portrait of the younger Tradescant to Harold Gilman’s ‘The Black Gardener’ to contemporary media images. True, the carved wooden figure of a gardener on the steps at Hatfield House holds a rake, not a spade – and at The Jolly Gardeners’ pub in Lambeth the figures on the pub sign pose with scythes – but over time the spade wins. It is a silver spade that you carry as the guest speaker at the Gardeners’ Society Court Dinner, I discovered. Why not a rake, or a fork, or a trowel? (And, okay, not a strimmer).

A spade is heroic. But it also has the most essential relationship with the earth. Gardening begins with digging a hole. And – as in the story of St Fiacre, digging a trench around his plot – making a garden is as much to do with giving a boundary to a space as it is with planting flowers and herbs.

Today St Fiacre should be the patron saint of the movement to explore the relationship between gardening and health. But history has given us too little to make us affectionate to him. And his feast day is on 11th August, a date by which our gardening spirits are in decline.

Perhaps we need a new patron saint? Saint Trad?

From next April, if you travel to the Museum by taxi, you will be able to tell your driver that inside the Museum is Britain’s only statue on public display of the patron saint of taxi drivers. And gardens. For now.