“The parks are the lungs of London.” – William Windham, 1808 For many Londoners, having our own gardens is an unattainable luxury, so this is where the city’s parks step in. Despite being the least likely people in the UK to have access to a private garden, people living in London are most likely to have a park nearby, with 44% of Londoners living within a five-minute walk of a park. William Pitt (the Elder) is said to have coined the phrase “Lungs of London” in the 18th Century, when the city’s three main parks – St James’s, Green and Hyde – were under threat from rapid urban expansion, and the idea of parks as “lungs” that benefit Londoners’ health and that must be protected has endured. But many of the green spaces that are so precious to us today have a battle-worn history of protests and petitions to ensure their protection. Inspired by our exhibition Lost Gardens of London, here we look at the history of three of London’s “saved” green spaces:

Hampstead Heath

“A sprawling north London parkland, composed of oaks, willows and chestnuts, yews and sycamores, the beech and the birch; that encompasses the city’s highest point and spreads far beyond it; that is so well planted it feels unplanned… with tickling bush grass to hide teenage lovers and joint smokers, broad oaks for brave men to kiss against, mown meadows for summer ball games, hills for kites, ponds for hippies, an icy lido for old men with strong constitutions”. – Zadie Smith, On Beauty

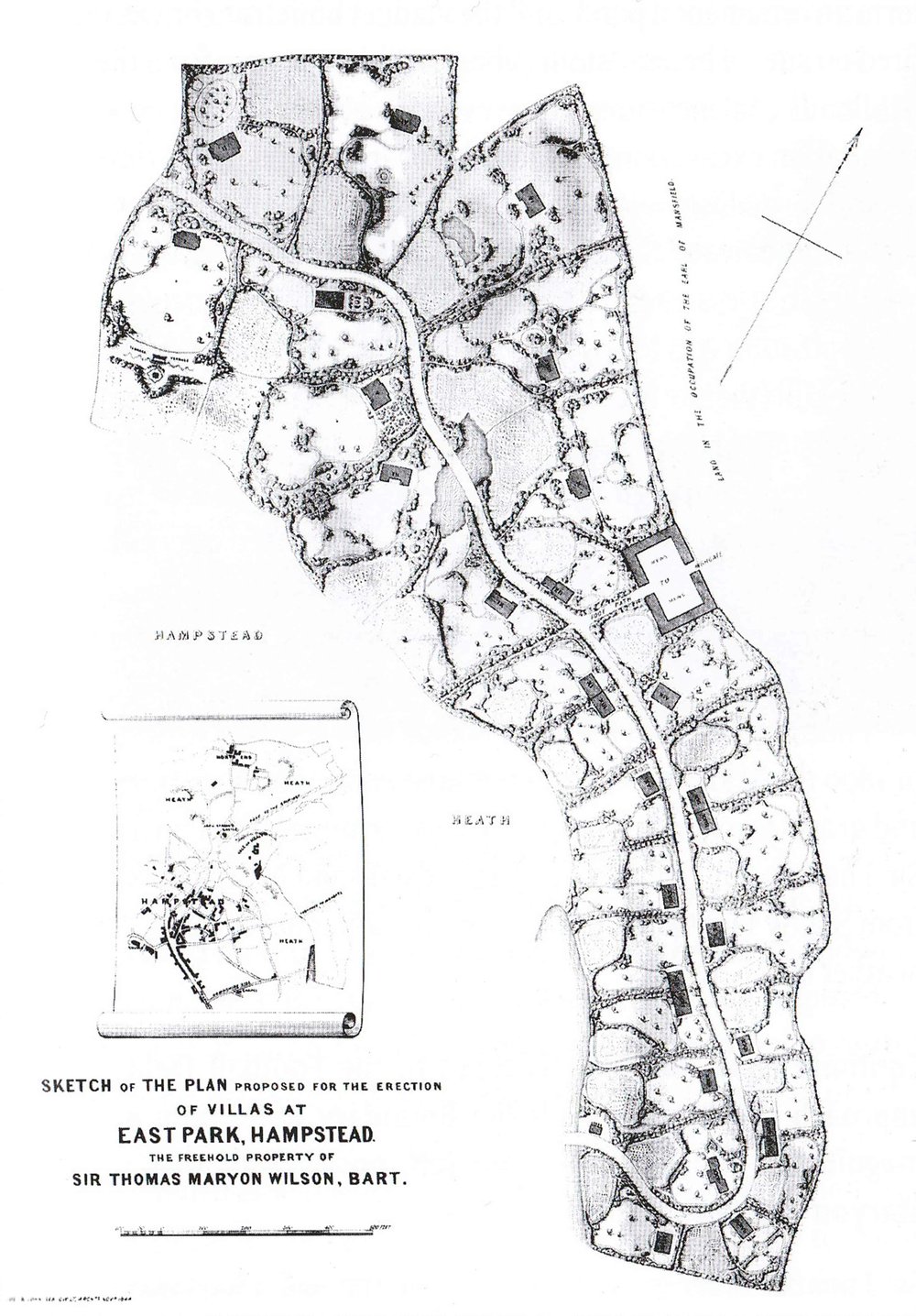

Star of poetry, literature, film and theatre, Hampstead Heath is a key player in the story of London’s parks. But there was a time when the ancient heath of woodland meadows was at risk of being snatched up for development. The Heath’s continued existence is thanks to a long fought battles by passionate campaigners, and the land was granted protected status just 150 years ago. In 1865 the Open Spaces Society, Britain’s oldest national conservation body, was established (then called the Commons Preservation Society) to preserve our commons for the enjoyment of the public. Founder members included John Stuart Mill and Octavia Hill (later founder of the National Trust). One of the Open Space Society’s first success stories was at Hampstead Heath, four miles north of central London. Hampstead Heath first appears in the history books in 1543, when its springs supplied London and when hunting and hawking were forbidden in the area to preserve game for King Henry VIII. By the 19th century, the heath was a popular destination for Londoners of all classes to escape the dirt of the city, and the views inspired painters and poets alike. This was cemented in 1860 with the opening of Hampstead Heath railway station. Meanwhile, Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson inherited most of the Heath from his father in 1821, and far from being an advocate for his parkland, Maryon Wilson saw pound signs. Years of legal battles ensued as he hoped to get permission to build on the land. His first attempts were thwarted, both in the name of public interest and perhaps more significantly (money talks), because his proposed developments would have blocked the views of the Heath enjoyed by several Hampstead gentry from their manors.

But our heathland villain was not giving up yet. Maryon Wilson pushed forwards with plans to build 28 villas in a section of the heath, similar to those already developed in Regent’s Park. Local sentiment was split between those who wanted to protect the park, and local tradesmen who thought the new villas would increase trade for the village. A viaduct was built with the intention of bypassing marshy swamp land and connecting to the meadowland the villas were to be built on. An ornamental pond was dug below the viaduct, but these were the only two parts of Maryon Wilson’s grand plan to materialise. Both still stand in Hampstead Heath today.

In response to Maryon Wilson’s attempts to carve up the heath for his personal profit, the Commons Preservation Society (CPS) fought years of legal battles and provided expert advice and representation to Hampstead’s residents. It wasn’t until Maryon Wilson’s death in 1869 that the matter was finally resolved. The land was passed to his brother John, was more public-spirited and agreed to the sale of 200 acres to the Metropolitan Board of Works.

On 29 June 1871, the Hampstead Heath Act enshrined in law that the 800 acres would be preserved as an open space for all to enjoy. The view from Parliament Hill to Westminster is also protected, you must be able to see St Paul’s Cathedral unobstructed from a specific spot on the hill. The Act declared that “It would be of great advantage to the inhabitants of the Metropolis if the Heath were always kept uninclosed and unbuilt on, its natural aspect and state being, as far as may be, preserved.”

Clissold Park, Stoke Newington

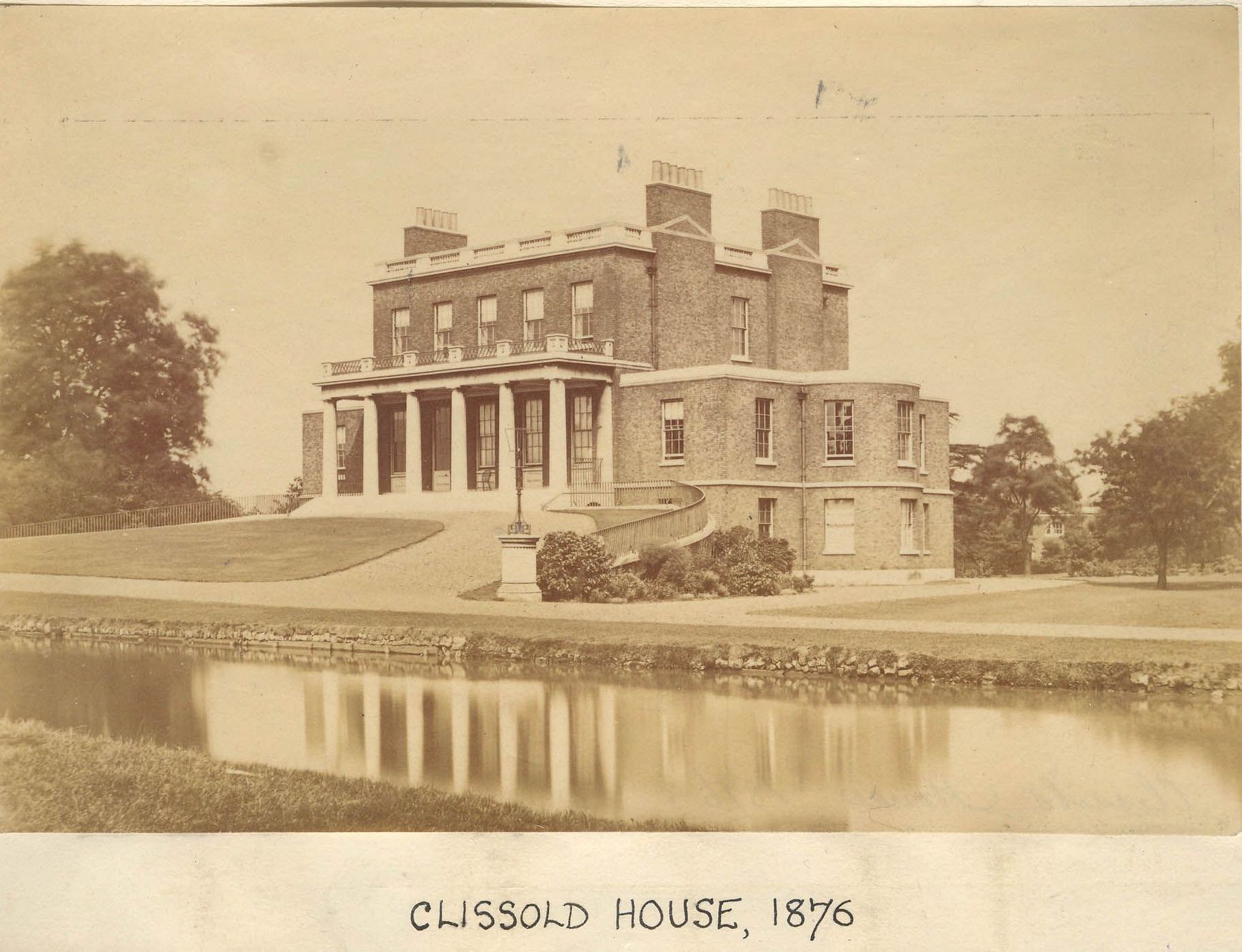

Samuel Hoare brought his family from Ireland to London in the mid-18th century. The family of successful bankers were Quakers, philanthropists and anti-slavery campaigners, with Samuel being one of the founders of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They settled in Paradise Row (now Stoke Newington Church Street), as the area of Stoke Newington was known in the 18th century as a hotbed of non-conformist religious views. His half-brother Jonathan Hoare had Clissold House (then Paradise House) built around 1790, designed to be his own idyll in the city. The house was surrounded by rural fields and meadows, and waterways weaving around the house fed by the New River, an artificial waterway that supplied the capital with clean water from Hertfordshire. Nearby Hackney had developed a thriving nursery trade, which supplied many of the rare and exotic trees and shrubs which were planted across the estate.

Fast-forwarding to 1811, industrialist William Crawshay bought the house and estate, and on his death in 1834 it was inherited by his daughter Eliza. She was now free to marry her sweetheart, local Swedenborgian priest Augustus Clissold, of whom her father had not approved. Clissold swiftly renamed the manor after himself. When Augustus Clissold died in 1882, the estate was sold to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for the purposes of building and development, and Stoke Newington was at risk of losing its green idyll. Like much of London, what was once a rural village had been transformed by the industrial revolution.

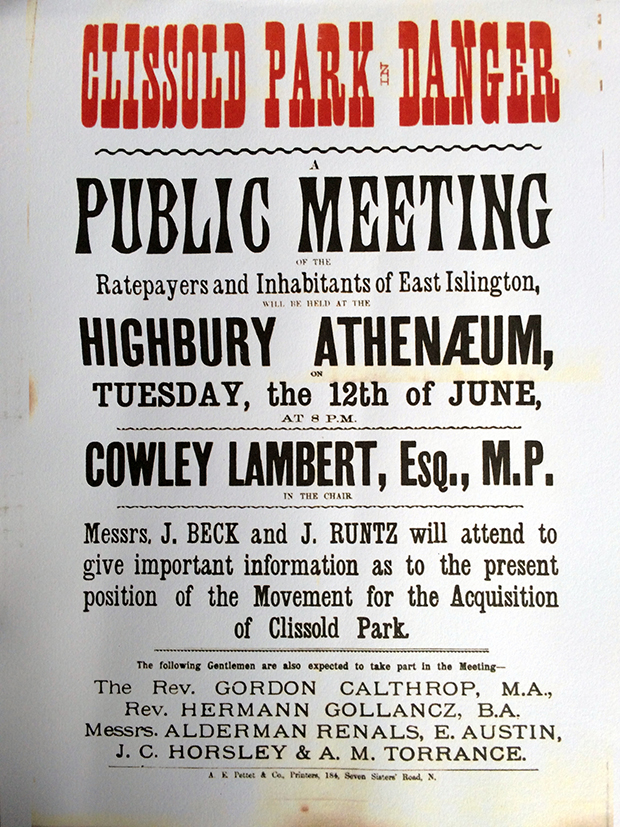

Luckily, local campaigners were on the case. Teaming up with the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association, they put forward a campaign to turn the land into a public park for the enjoyment of local residents, and to save the rare trees and ecology of the park. Finsbury Park had been opened a mile north in the 1860s, and Stoke Newington residents were keen for a park of their own. The petition was signed by 12,000 people and Clissold Park was officially opened to the public on 24 July 1889.

The two ponds in the park are named the Beckmere and the Runtzmere in honour of two major campaigners, Joseph Beck of The City of London and John Runtz of the Metropolitan Board of Works.

Hilly Fields, Brockley

“We all want quiet. We all want beauty… we all need space.” – Octavia Hill, co-founder of the National Trust

In Lewisham, south east London, Hilly Fields stands proudly 175 feet above sea level with views across the city. And once again we have Octavia Hill, co-founder of the National Trust, to thank for its survival.

In the late 19th century, the farmland in the Brockley area around Hilly Fields was being rapidly built up, as the sprawl of the city stretched further south. At the time, as part of her mission to improve working class living conditions, Octavia was buying neglected properties in London, overhauling them and transforming their tenants’ lives. As she wrote in her article ‘Space for the People’ (1883), Octavia was visiting tenants in nearby Deptford one day, when she noticed a vase of freshly picked flowers. The tenant informed her that the flowers had been picked on Hilly Fields, so Octavia was inspired to visit the area on the same day.

She learned that plans were afoot to develop the land on Hilly Fields, and nearby Deptford Common had already been built over. So she formed a committee of influential people to save the space, raising subscriptions from generous benefactors including William Morris, the Duke of Westminster, and many of the City Livery Companies, such as the Goldsmiths’, Fishmongers’ and Leathersellers. As a result of the campaign and the donations raised, London City Council was able to purchase the park and it opened to the public on 16 May 1896.

—