An update on the Benton End Walled Garden appeal

28 Oct 2025

Garden Museum awarded grant by the National Lottery Heritage Fund to restore Benton End House and Gardens

28 Oct 2025

Benton End: Help us restore the walled garden of Cedric Morris

6 Jun 2025

Benton End appoints new Project Director and Trustee

6 Jun 2025

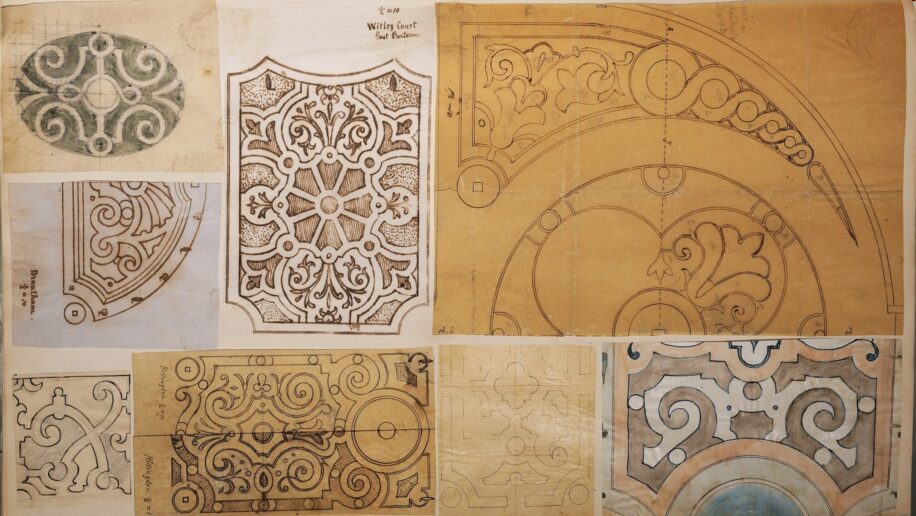

Garden Museum acquires the archives of the great Victorian landscape architect William Andrews Nesfield

12 Dec 2024

Save the Mortlake tapestry and put our earliest image of a female gardener on display

28 Oct 2024

A Sponsored Swim for Lambeth Green: An update from the halfway point

11 Oct 2024

Remembering Alex Fortescue: 1968–2024

20 Jun 2024

Update: Success in our campaign to change London’s policy on minimum sunlight levels in green spaces

28 Jul 2023

New Acquisition: a 17th-century Mortlake tapestry depicting gardens in March

25 Jul 2023

Her Majesty The Queen officially opens British Flowers Week 2023

9 Jun 2023

Rupert Tyler appointed the Garden Museum’s next Chair of the Board of Trustees

12 Apr 2023

Garden Museum Chair Mark Fane stepping down after 12 years

11 Nov 2022

‘Old Paradise Gardens? Where’s that?’

25 Feb 2022

The Garden Museum announces plans to revive Cedric Morris’ Suffolk home Benton End as a centre of art and gardening

1 Nov 2021

Alan Titchmarsh MBE inaugurated as the new President of the Garden Museum

25 Oct 2021