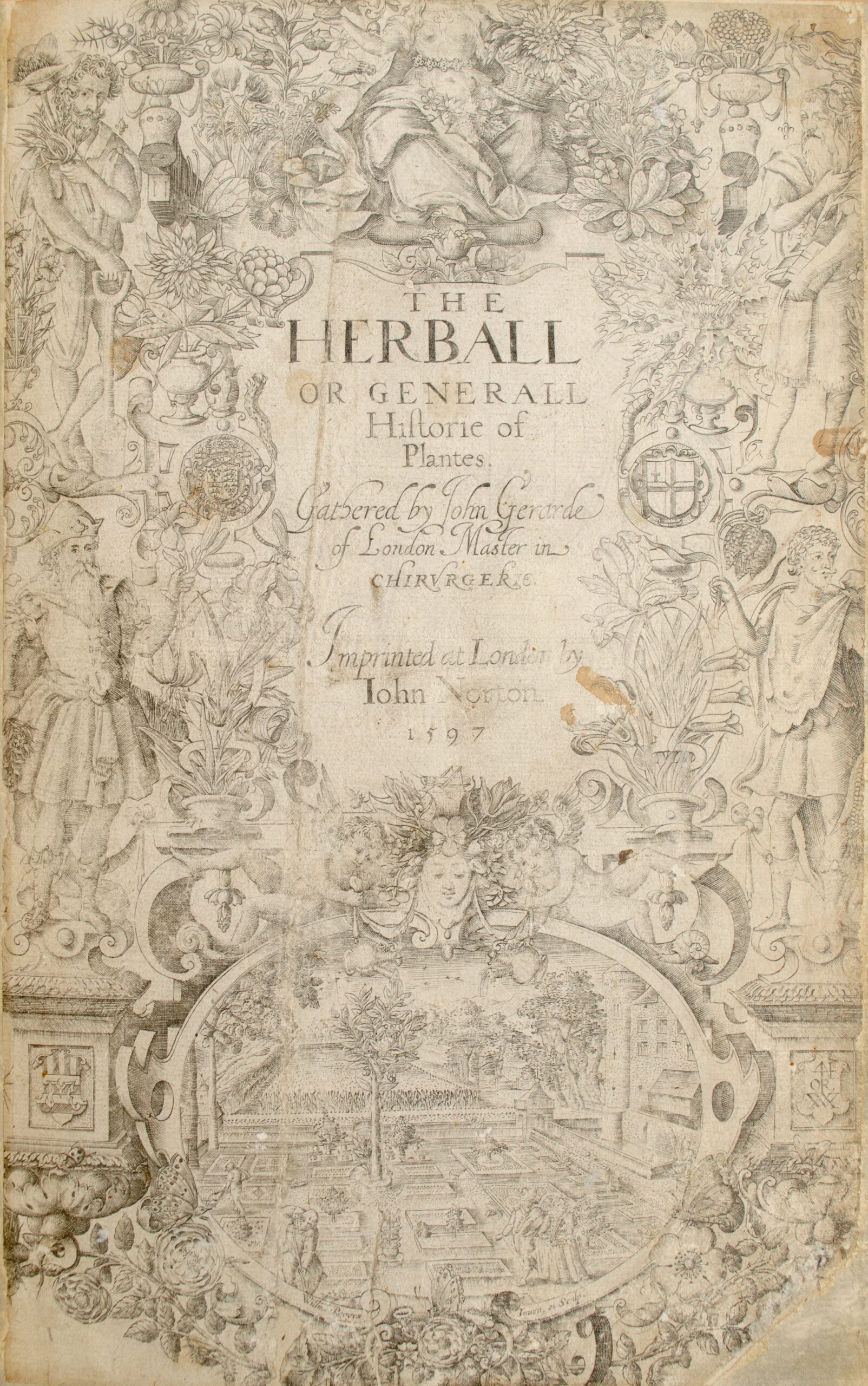

John Gerard (1545–1612) was a herbalist in charge of several important gardens including those of William Cecil, Lord Burghley and the Physic Garden at the College of Physicians. He also had his own garden in Holborn, London, which “grew all manner of strange trees, herbes, rootes, plants, flowers and other such rare things”.

He published The Herball of Generall Historie of Plantes in 1597. Jarman owned a copy and it was one of the books that inspired him as a gardener. Printed herbals were used by apothecaries to guide them when making pills and medicines described by physicians and he used it to research the plants he found growing on the ness as well as those he collected further afield for the garden at Prospect Cottage.

On Tuesday 21 March 1989, Jarman recorded in his journal

“…Deep in the middle of the woods, in the most secret glade, primroses are blooming, the only ones I have found; but there are carpets of violets almost hidden by their bright green leaves.

The unobservant could walk by them without noticing as the leaves and flowers create an almost perfect camouflage, the elusive purple vanishing in the green.”

The next day on Wednesday 22 March 1989 he noted that

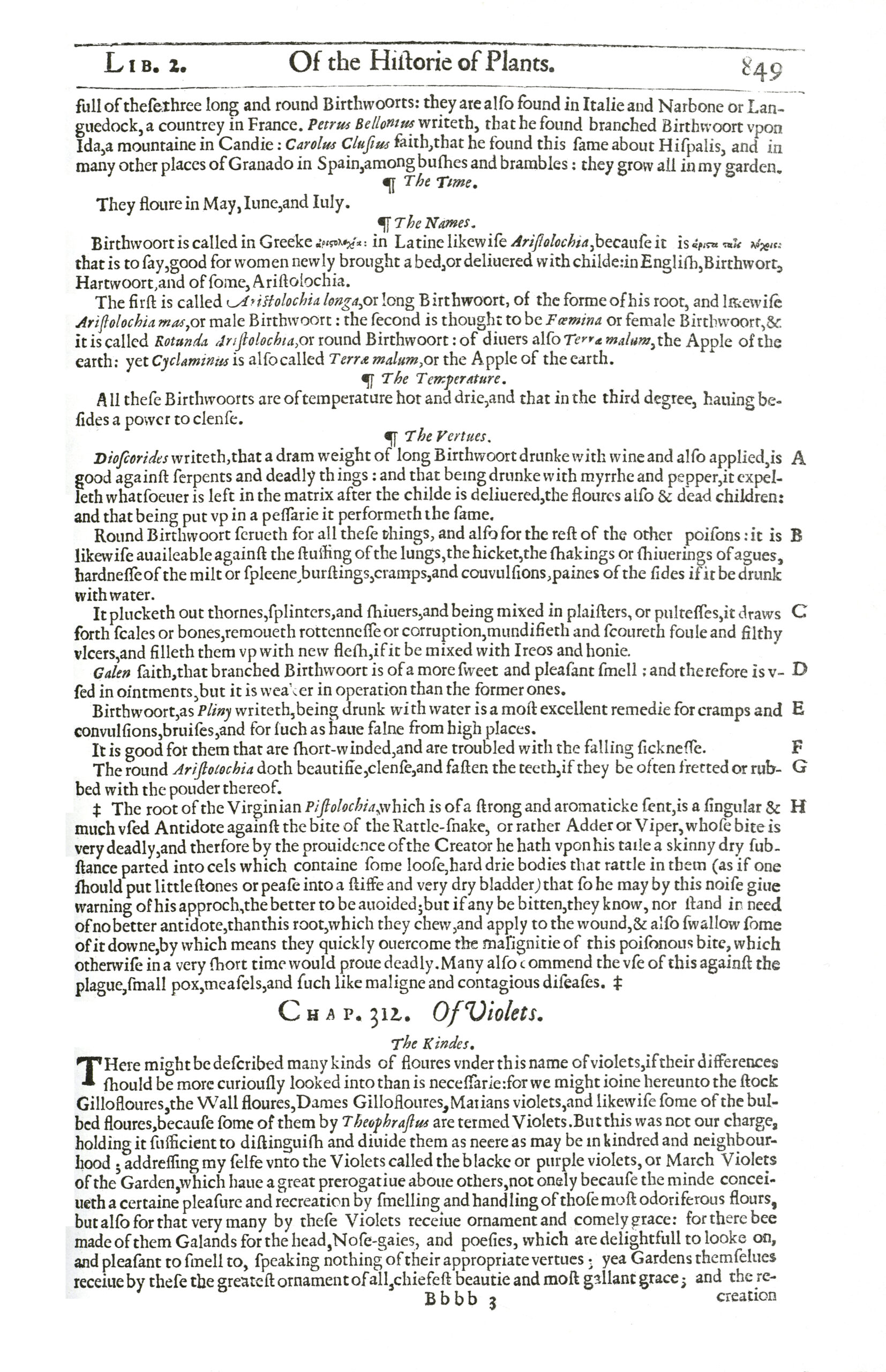

“Gerard says of violets – that they:

Stirre up a man that which is comely and honest; for flowers through their beauty, variety of colour, and exquisite forme, do bring to liberal and gentle manly minde, the remembrance of honesty, comlinesse and all kinds of virtue, because it would be an unseemly and filthy thing (as a certain wise man sayeth) for him that look upon and handle faire and beautiful things to have his mind not faire, but filthy and deformed.”

Click on the gallery images throughout to view in more detail.

Violets had been a favourite of Jarman’s since his childhood and he remembered in his journal finding them when he was at boarding school.

“The violet held a secret. Along the hedgerow that ran down to the cliffs at Hordle deep purple violets grew – perhaps no more than a dozen plants. I stumbled across them late one sunny March afternoon as I came up the cliff path from the sea. They were hidden in a small recess. I stood for some moments dazzled by them.

Day after day I returned from the dull regimental existence of an English boarding school to my secret garden – the first of many that blossomed in my dreams…..Term ended. I bought myself violets from the florist’s and put them by my bedside. My grandmother disapproved of flowers in the bedroom, said they corrupted the air. Violets, she said, were the flower of death.

But the violet, I discovered, was third in the trinity of symbolic flowers, flower of purity,

Whose virtue neither the heat of the sun melted away,

Neither the rain has washed and driven away.

The violet, Nothing for behind the best for smelling sweetly, a thousand more will provoke your content.

A new orchard garden was mine.

That summer, when the wheat had grown waist high, we carved a secret path from the violet grove into the centre of the field, and lay there chewing the unformed seeds, rubbing ourselves all over each other’s bronzed and salty bodies, such was our happy garden state.”

Jarman was welcomed by the community in Dungeness and on Saturday 25 March 1989 he recorded that

“My neighbours brought me a purple sage the first gift the garden has received. It grows apace.

Salvia salvatrix, sage the saviour. ‘He that would live for aye must eat sage in May’. A man’s business thrives or falls like the herb in his garden. Pepys writes in his diary that he saw a churchyard in which sage was grown on every grave. Gerard says:

Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy and taketh away shakey trembling members.

Sage attracts toads. Boccaccio’s toad that lived under the sage bush was one of a long line.

Thomas Hill writes:

Serpents greatly hate the fire, not for the same cause, that this duleth their sight, but because the nature of fire is to resist poison, they also hate the strong savour far flying the garlike and red onions procure. They love the savin tree, the ivy and fennel as toads do sage, and snakes the herb rocket, but they are mightily displeased and sorest hate the ash tree, in so much as the serpents neither to the morning nor the longest evening shadows of it will draw near, but rather shun the same and fly far off.

In the evening I walked to the Long Pitts, the violets under the ash tree glimmering in the dusk. No serpents about, just the hum of the power plant.”

On Monday 1 May 1989 Jarman noted

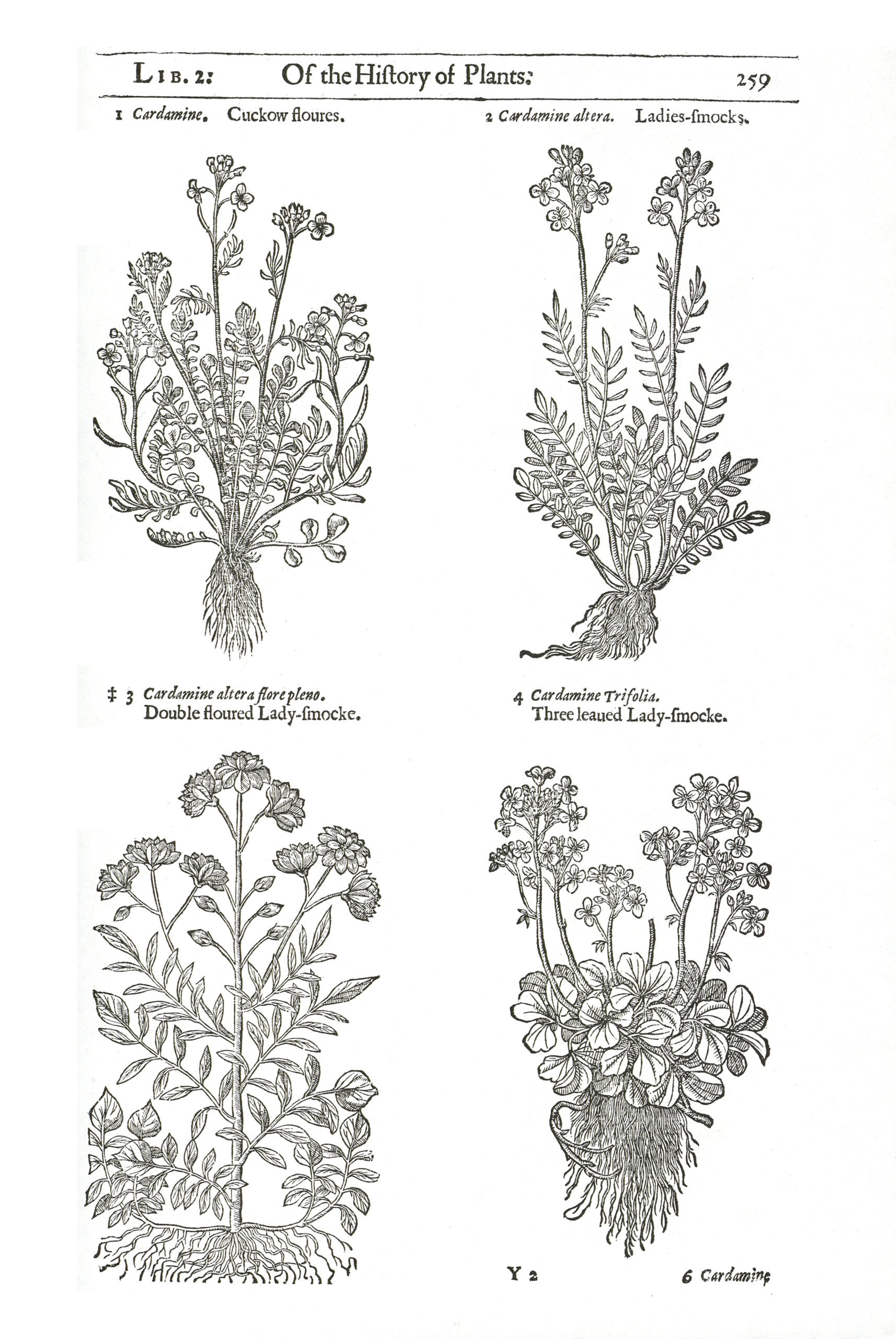

“A cuckoo echoes across the marshes. I took a long walk this evening and in the dying light discovered a patch of periwinckle deep in the woods I’ve never notice before perhaps as its only just come into flower. The alexanders are full out and near them I found a near white wild pansy the only one I saw. The island of bracken is unfolding and by one of the old mine craters a Lady’s smock was in flower. The sloe blossom and pear are almost over the full loose webs of the devastating brown tail-moth are being spun. May day warm and overcast neither an indoor or outdoor day – strangely lethargic my purple iris finally opened. Before turning in, I watered the garden, as I’m away for ten days and the forecast is for warm weather.”

Gerard mentions the Lady’s smock called in Latine Flos Cuculi in English cuckoo flower: in Norfolk Canterbury bella: at Namptwich in Cheshire my native county Lady’s smockes, which have cased me to name it after their fashion.

On Saturday 20 May Jarman wrote that he had

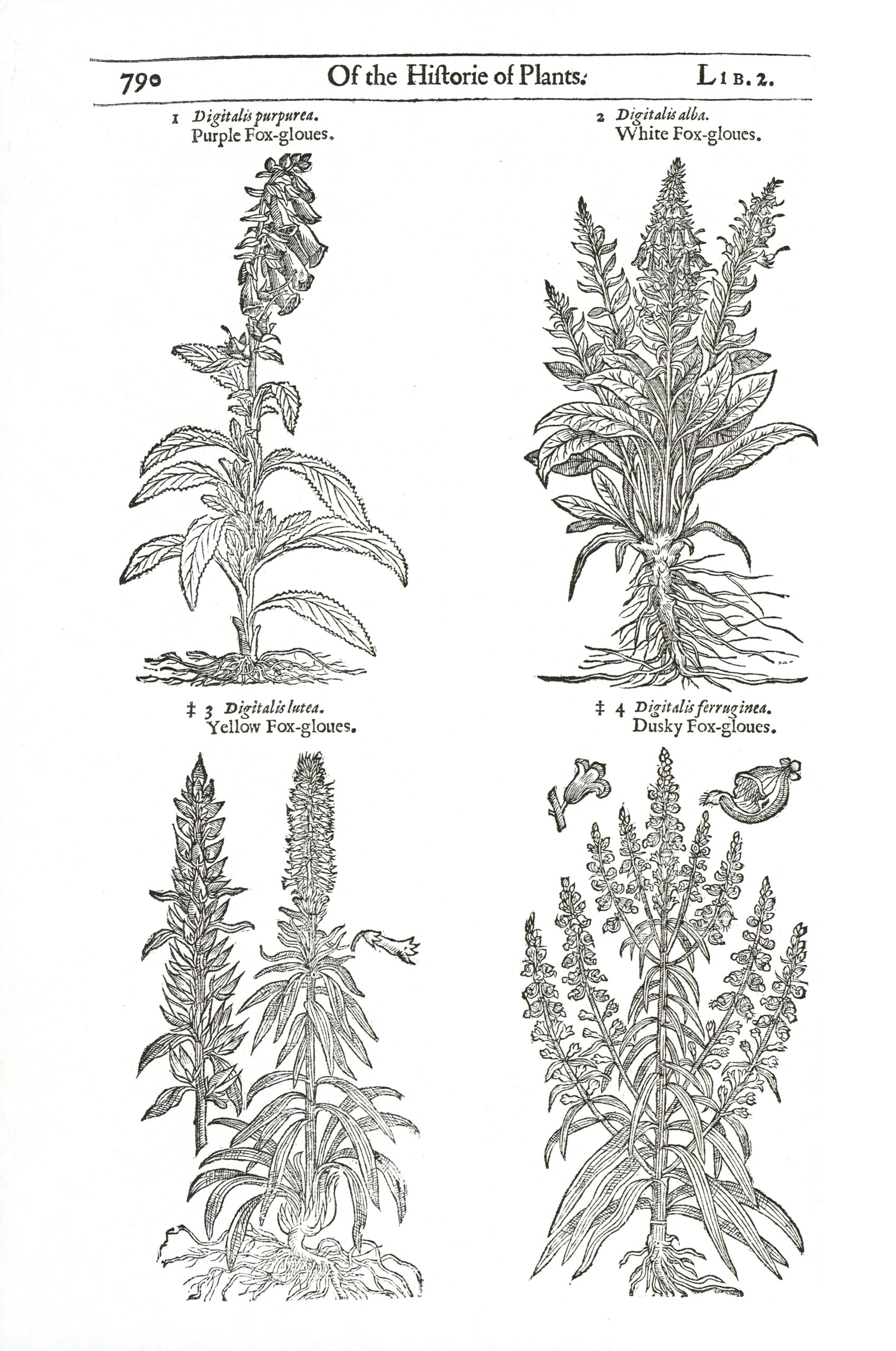

“always thought of foxgloves as a flower of the woods – deep in the shade, beloved of the bumble bee and little people. But the foxgloves of the Ness are a quite different breed. Strident purple in the yellow broom, they stand exposed to wind and blistering sunshine, as rigid a guardsmen on parade.

There they are at the edge of the lakeside, standing to attention, making a plash – no blushing violets these, and not in ones or twos but hundreds, proud regiments marching in the summer, with clash of cymbals and rolling drums. Here comes June. Glorious, colourful June.

The foxglove, Digitalis pupurea, folksglove, or fairyglove whose speckles and freckles are the marks of elves’ fingers, is also called dead man’s fingers. It contains the poison Digitalis, first used by Dr Withering in the 18th century to cure heart disease. Foxglove is hardly mentioned in older herbals – Gerard says, it has no use in medicine, being hot and dry and bitter. The glove comes from the Anglo-Saxon for string bells, ‘gleow’.”

On Saturday 27 May Jarman noted

“Nearly all the flowers that grow so abundantly on our shingle find a place in folklore or herbals.

The petals of the red poppy were once collected on sunny days and made into a syrup; while the seeds are scattered over bread – the Romans mixed them with honey and ate them like jam. The poppy is rarer than it once was. Gerard wrote The fields are garnished and overspread with these wild poppies.”

Jarman was drawn to the folklore and history of plants that surrounded them. Before starting his art studies at the Slade School of Fine Art his father had insisted he study something more academic. So he had read English and History at King’s College London.

Whilst this delay in starting his formal training as an artist had antagonised him it ensured a lifelong interest in literature and history. Gerard’s Herball introduced him to regional names and the historical medicinal uses for plants. On quiet evenings he would take a walk around the ness and then return to his herbals to look up the entries of the plants he had seen and taken cuttings from. His garden and its plants were layered with stories and meanings contained within Gerard’s Herball and the other herbals he owned. His love of history and literature enabled him to seamlessly weave the historical stories of plants into his journals and into Modern Nature the book he published on the garden.