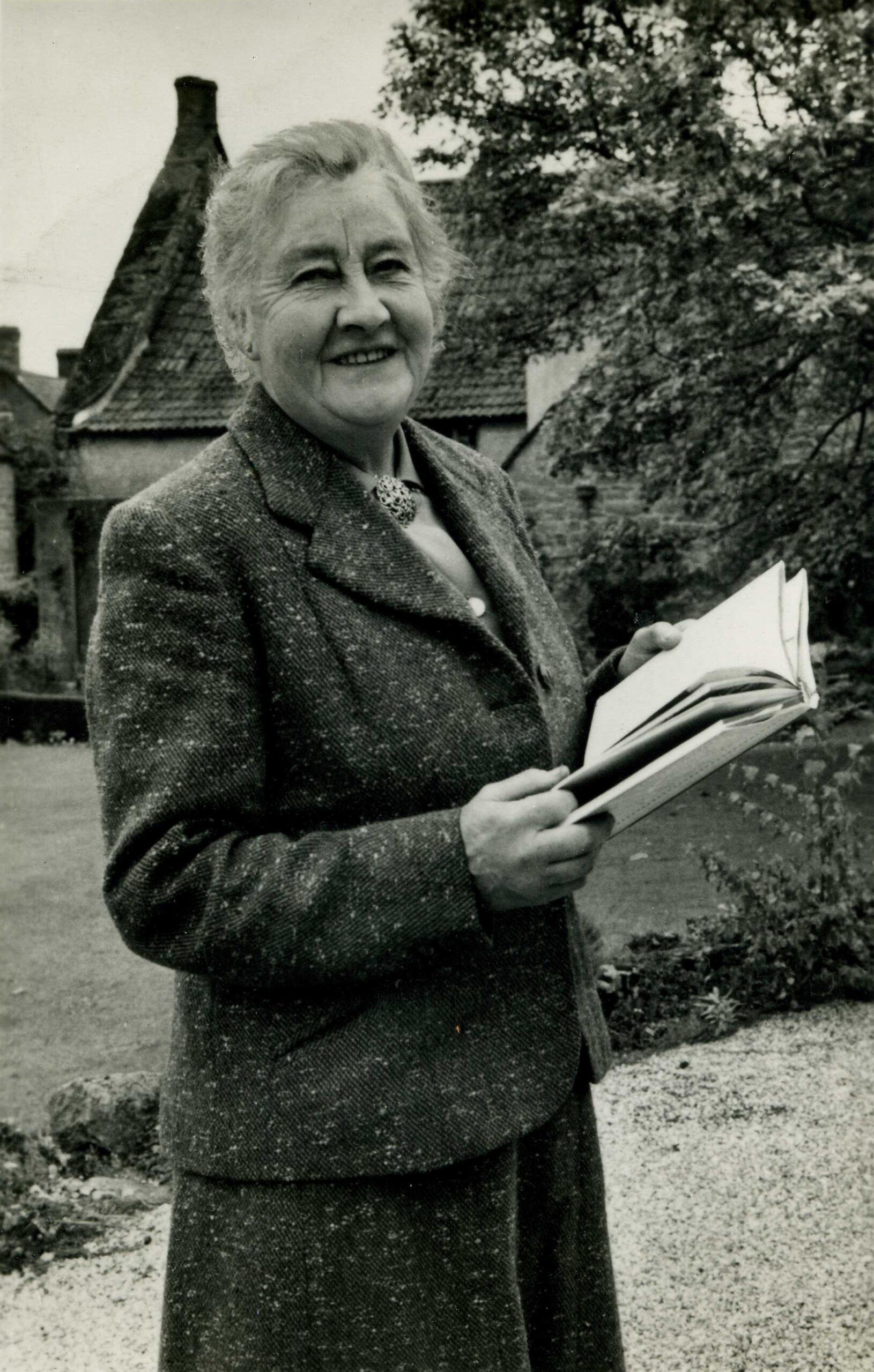

By Ella Finney, Assistant Curator. All images Garden Museum collection Margery Fish (1892-1969) is best known for her books about creating her cottage garden at East Lambrook Manor in Somerset. It is here that much of her hugely popular and influential experimentation with the informal English cottage garden style took place, and from which much of her garden writing stemmed. Margery was born in 1892 in Hackney, London. After graduating from secretarial college, she spent twenty years working in Fleet Street, first with the countryside magazines and then with Associated Newspapers. She travelled to the United States during World War I on a war mission with editor of the Daily Mail, Lord Northcliffe, a major innovator in popular journalism at the time. She went on to work for six successive editors of the Daily Mail, the last of whom, Walter Fish, she married in 1933.

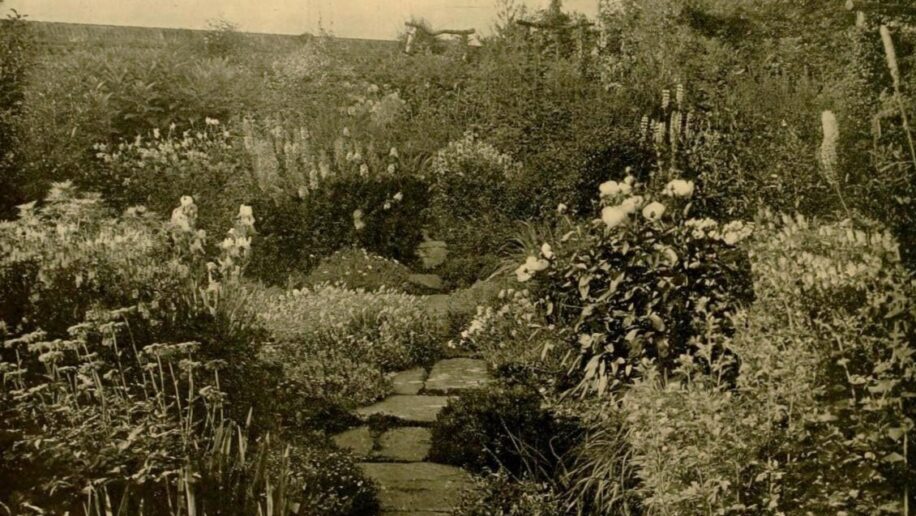

Purchased as a retreat from London in the looming shadow of World War II in 1937, Lambrook Manor became the beloved project of Margery and her husband. Their friends looked on in skepticism – “how would two Londoners go about creating a garden from a farmyard and a rubbish heap?” The answer: with a few bumps along the way. Humorously detailed in Margery’s semi-autobiographical, semi-instructional book We Made a Garden (published in 1965), you can imagine her writing with a twinkle in her eye, as she detailed their clashing styles and battle of wills. Evoking a fairy’s glen, the gardens of Lambrook Manor are a far cry from London’s industrial landscape. How did Margery, a London native and adventurous city slicker, not to mention a completely novice gardener, become renowned for one of the most archetypal cottage gardens in England? The garden she created there is Grade I listed in 1992 and remains open to the public.

Walter favoured formal displays with bright summer flowers. Margery writes, “I learnt a great deal from Walter that first year of gardening. The first thing I learnt was that he knew a great deal more about the subject than I thought he did.” He had a stringent approach. Margery laments the fatal outcome of one of Walter’s gardeners who had had “one joy in life and that was to grow wonderful chrysanthemums,” so much so that the gardener had neglected the rest of the garden. Walter took a knife in remonstrance to the prized blooms, slashing the “pampered darlings” dead. Margery swore to take a measured approach to her garden from that point onwards. However, Walter was 18 years Margery’s senior, and on his death in 1947, Margery was left to fully implement her own ideas and develop her own skills as a plantswoman. After World War II, labour had become scarce and expensive, and it became unrealistic to have paid gardeners. Margery gardened her own garden, and for this reason her advice is always reasonable and practical.

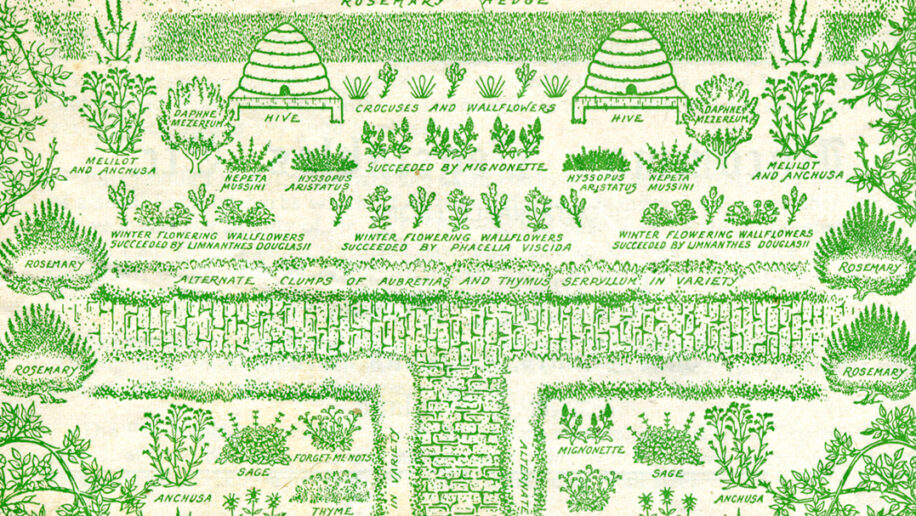

Margery’s distinctive gardening style emerges when looking through the long list of titles she published, including A Flower for Every Day (1958), Gardening in the Shade (1964) and Carefree Gardening (1966). Her approach was informal with a focus on shade-loving plants and early spring flowers, allowing for self-spreading and self-seeding native plants, and always keeping in mind the winter garden. ‘Apart from the calm of the lawn and some old fruit trees there was the noted ditch garden, bosky corners, retaining walls and rock edges: everything was done to make her plants feel at home.’ – Graham Stuart Thomas on Margery Fish’s garden at Lambrook Manor

These included the snowdrop, of which she built up a world-class collection of species and varieties. Like the artist John Morley, who work was displayed at the Garden Museum in the exhibition John Morley: Artist Gardener, she was a galanthophile. Her garden was filled with snowdrops. Margery liked green flowers, especially green-marked snowdrops. She championed the doubles, such as Galanthus ‘Ophelia’, because they open even in dim light. She loved Galanthus ‘Magnet’ with its wiry pedicels, the pearls dancing ‘en tremblant’ like jewellery. She was not a fan of the rare and pricey yellow snowdrops, although she kept Galanthus nivalis f. pleniflorus ‘Lady Elphinstone’ in a trough on the sunny side of the Malthouse at Lambrook Manor. Her snowdrops really came into their own in winter where they were planted in her garden in a sheltered corner at the bottom of a steep bank, amongst winter cyclamen, large crocuses and leucojums.