By Jane Harrison, Project Archivist: Beth Chatto Archives

In a project funded by by Archives Revealed, funded by The National Archives, The Pilgrim Trust and The Wolfson Foundation, Jane Harrison has been cataloguing the archive of Beth Chatto deposited at the Museum and sharing her discoveries. Here she shares the photographs and drawings which tell the story of how Beth became the country’s leading advocate of ecological gardening: Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden is internationally known and has inspired many similar gardens but originally it was something of an experiment in horticulture for her: taking the poor soil and relatively extreme conditions of the area as an opportunity to create a garden of drought tolerant plants. However, it was not created in isolation. Beth had been planting her gardens using her knowledge of plant habitats for decades, with planting based on ecological principles, and design based around her long experience of arranging flowers and plants.  Photo of the family dog sitting on the garden path with note on the back by Beth: “Great Chesterford – Essex, about 1934. The garden of my childhood where I had a little corner of my own. Observe the well head! There was no running water – we let down the bucket on a chain.” While Beth inherited her parent’s love of gardening and was cultivating her own small patch garden from an early age, she credited her friendship with her future husband Andrew Chatto with opening her eyes to the idea that plants in the garden would have natural habitats in which they thrive. An early example of this interest can be found in Beth’s major college project, a botanical survey of plants in salt marshes of the Colne estuary. Beth had noticed that there were different types of plants in certain areas depending on whether the water was saltier or fresher and asked for Andrew’s help to devise and carry out the project. They identified several sites and marked out a series of quadrats, working from the mouth of the river where the water was saltiest and taking note of location, climate, exposure and soils before carefully recording the plants that were present. The project took them two years to complete but the result confirmed Beth’s theory about plant associations in the estuary.

Photo of the family dog sitting on the garden path with note on the back by Beth: “Great Chesterford – Essex, about 1934. The garden of my childhood where I had a little corner of my own. Observe the well head! There was no running water – we let down the bucket on a chain.” While Beth inherited her parent’s love of gardening and was cultivating her own small patch garden from an early age, she credited her friendship with her future husband Andrew Chatto with opening her eyes to the idea that plants in the garden would have natural habitats in which they thrive. An early example of this interest can be found in Beth’s major college project, a botanical survey of plants in salt marshes of the Colne estuary. Beth had noticed that there were different types of plants in certain areas depending on whether the water was saltier or fresher and asked for Andrew’s help to devise and carry out the project. They identified several sites and marked out a series of quadrats, working from the mouth of the river where the water was saltiest and taking note of location, climate, exposure and soils before carefully recording the plants that were present. The project took them two years to complete but the result confirmed Beth’s theory about plant associations in the estuary.  A page from Beth’s notebook, showing one of the quadrats she used for her project. While the diagram is very concise and easily understood (even upside down) while the notes around it are more descriptive, showing a similar style to her later writing. For example on the right of the page Beth observes ‘The whole meadow is starred with the white Cochlearia flowers, the first plant to be in full blossom of the new year’. This notebook is still held by the Chatto family. The couple married in 1943 and settled into married life at Andrew’s parents’ house ‘Weston’ in Colchester. The gardens were quite formal and rather traditional, apart from a rockery and wild garden which Andrew had developed himself. Over time Beth began to take over the gardens, firstly the vegetable plot and later the rest, replacing traditional garden flowers with grey foliage which Andrew recommended as better for the location.

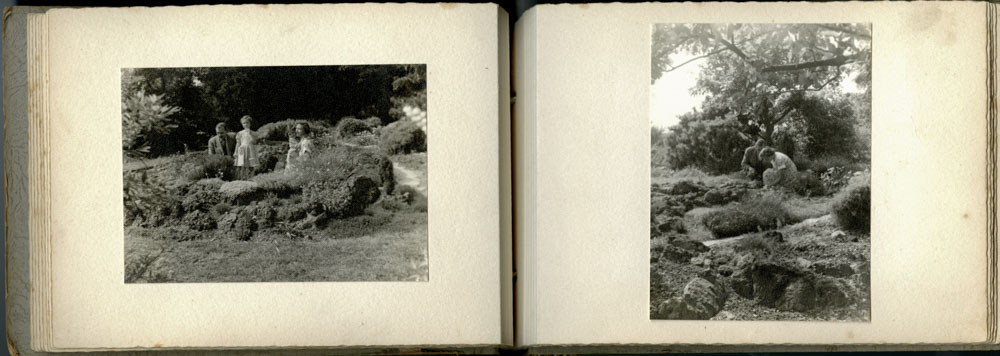

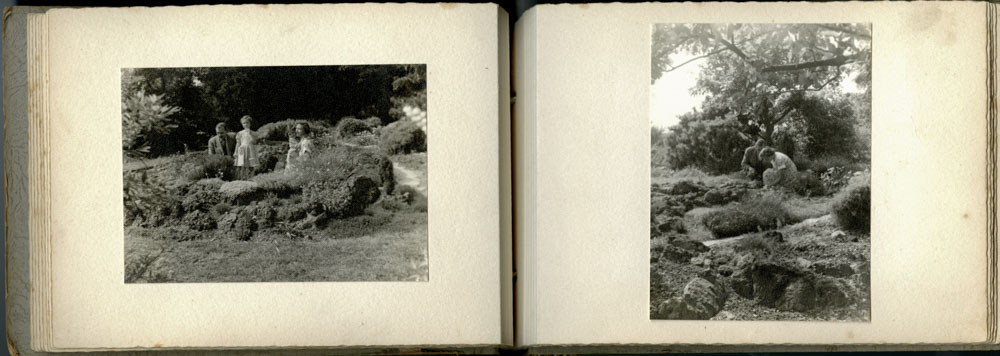

A page from Beth’s notebook, showing one of the quadrats she used for her project. While the diagram is very concise and easily understood (even upside down) while the notes around it are more descriptive, showing a similar style to her later writing. For example on the right of the page Beth observes ‘The whole meadow is starred with the white Cochlearia flowers, the first plant to be in full blossom of the new year’. This notebook is still held by the Chatto family. The couple married in 1943 and settled into married life at Andrew’s parents’ house ‘Weston’ in Colchester. The gardens were quite formal and rather traditional, apart from a rockery and wild garden which Andrew had developed himself. Over time Beth began to take over the gardens, firstly the vegetable plot and later the rest, replacing traditional garden flowers with grey foliage which Andrew recommended as better for the location.  A page from a family photo album showing the Chatto family in the rockery and wild garden created by Andrew at ‘Weston’. c.1952, taken by Daniel Osbourne. The Chattos added to their garden with cuttings brought back from their travels and given to them by friends such as the painter and gardener Cedric Morris. Morris was generous with both the rare plants from his garden and with his knowledge of planting. It was he, as Beth recalled in later years, who suggested that if she would never be able to create a garden at Weston with the range of plants she wanted.

A page from a family photo album showing the Chatto family in the rockery and wild garden created by Andrew at ‘Weston’. c.1952, taken by Daniel Osbourne. The Chattos added to their garden with cuttings brought back from their travels and given to them by friends such as the painter and gardener Cedric Morris. Morris was generous with both the rare plants from his garden and with his knowledge of planting. It was he, as Beth recalled in later years, who suggested that if she would never be able to create a garden at Weston with the range of plants she wanted.  Andrew Chatto discussing a plant with Cedric Morris, c.1970s. Beth and Andrew took his advice in 1959, building a new house on the edge of Andrew’s fruit farm, where the land was considered too poor for farming. As the land was so variable Beth took the opportunity to create a series of different gardens for the different conditions, placing plants where they grew best and arranging them decoratively rather than trying to recreate whole habitats. She continued this approach when she opened the ‘Unusual Plants’ nursery in 1967, using her garden as a living catalogue and dividing the plants for sale by recommended conditions to allow visitors to pick those which suited their gardens. At the time this approach was unusual and one she used to great effect when she began creating displays for the RHS flower shows.

Andrew Chatto discussing a plant with Cedric Morris, c.1970s. Beth and Andrew took his advice in 1959, building a new house on the edge of Andrew’s fruit farm, where the land was considered too poor for farming. As the land was so variable Beth took the opportunity to create a series of different gardens for the different conditions, placing plants where they grew best and arranging them decoratively rather than trying to recreate whole habitats. She continued this approach when she opened the ‘Unusual Plants’ nursery in 1967, using her garden as a living catalogue and dividing the plants for sale by recommended conditions to allow visitors to pick those which suited their gardens. At the time this approach was unusual and one she used to great effect when she began creating displays for the RHS flower shows.  The printed plant list for Beth’s first exhibit at Chelsea in 1976, dividing the plants by habitat. At previous smaller shows she had used a simple typed list of plants but for Chelsea everything was properly printed. She exhibited at RHS Westminster Hall in 1975 and made her first appearance at Chelsea the following year. She only had a small stand but she made the most of it, grouping the plants by damp and dry areas as this sketched plan depicts and re-creating her garden in microcosm with the same naturalistic style.

The printed plant list for Beth’s first exhibit at Chelsea in 1976, dividing the plants by habitat. At previous smaller shows she had used a simple typed list of plants but for Chelsea everything was properly printed. She exhibited at RHS Westminster Hall in 1975 and made her first appearance at Chelsea the following year. She only had a small stand but she made the most of it, grouping the plants by damp and dry areas as this sketched plan depicts and re-creating her garden in microcosm with the same naturalistic style.  A sketch plan for a possibly layout for her exhibit at Chelsea, 1976. The dry area is marked by paving stones and the damp with a small pool but it is also possible to see the same split in the names here as in the plant list. Her plants were remarked on as unusual for several reasons: they were mostly foliage plants and arranged as though in a garden, and that they were not particularly hard to grow. Unlike some of the other exhibits, here people could imagine how the plants might look in their own gardens and have a reasonable chance growing them successfully. It was a very dry summer so her plants for dry environments were particularly noted. She was approached by Graham Rose, a journalist for the Sunday Times and asked to design two beds for dry areas for an article, almost on the spot. She credits this article as the point where Unusual Plants became a national brand. Other journalists followed, including one she found skulking around the nursery beds and almost had escorted from the premises. Among her many admirers were several famous people with an interest in plants, including Baron Philippe de Rothschild and the musician George Harrison and his wife Olivia. Rothschild took her off for a weekend to see the gardens of his Chateau while Harrison offered her a full-time job. She went to France but declined any offers of full-time work: her own gardens were her passion and her priority. She was still happy to offer advice to those who asked, such as Wendy Ellis Somes, prima ballerina of Royal Ballet, who she instructed to look at gardens around her and consider her own landscape.

A sketch plan for a possibly layout for her exhibit at Chelsea, 1976. The dry area is marked by paving stones and the damp with a small pool but it is also possible to see the same split in the names here as in the plant list. Her plants were remarked on as unusual for several reasons: they were mostly foliage plants and arranged as though in a garden, and that they were not particularly hard to grow. Unlike some of the other exhibits, here people could imagine how the plants might look in their own gardens and have a reasonable chance growing them successfully. It was a very dry summer so her plants for dry environments were particularly noted. She was approached by Graham Rose, a journalist for the Sunday Times and asked to design two beds for dry areas for an article, almost on the spot. She credits this article as the point where Unusual Plants became a national brand. Other journalists followed, including one she found skulking around the nursery beds and almost had escorted from the premises. Among her many admirers were several famous people with an interest in plants, including Baron Philippe de Rothschild and the musician George Harrison and his wife Olivia. Rothschild took her off for a weekend to see the gardens of his Chateau while Harrison offered her a full-time job. She went to France but declined any offers of full-time work: her own gardens were her passion and her priority. She was still happy to offer advice to those who asked, such as Wendy Ellis Somes, prima ballerina of Royal Ballet, who she instructed to look at gardens around her and consider her own landscape.  A card sent by George and Olivia Harrison to Beth with a large bouquet after her announcement that she would be unable to exhibit at Chelsea in 1982. She was immensely touched by the gesture and still told the story years later. Image by kind permission of Olivia Harrison. The Gravel Garden was the culmination of Beth’s ideas, to create a garden so well suited to its environment it did not need watering by anything but the rainfall. She already had several decades of practical experience in ecological planting, and used her travels and acquaintances for inspiration, taking the overall design from dry riverbeds she had seen abroad. Another influence was her visit to Dungeness with Christopher Lloyd: they wandered into the garden created by film maker Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage and spoke to the man himself.

A card sent by George and Olivia Harrison to Beth with a large bouquet after her announcement that she would be unable to exhibit at Chelsea in 1982. She was immensely touched by the gesture and still told the story years later. Image by kind permission of Olivia Harrison. The Gravel Garden was the culmination of Beth’s ideas, to create a garden so well suited to its environment it did not need watering by anything but the rainfall. She already had several decades of practical experience in ecological planting, and used her travels and acquaintances for inspiration, taking the overall design from dry riverbeds she had seen abroad. Another influence was her visit to Dungeness with Christopher Lloyd: they wandered into the garden created by film maker Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage and spoke to the man himself.

Letter sent by Derek Jarman to Beth Chatto after their meeting at Dungeness. Jarman described in his diary how after he recognised Beth he ‘almost fell off the Ness’ in surprise. Their visit and this list helped to inform and inspire the Gravel Garden. Jarman had heard of Beth Chatto and was impressed with her knowledge of plants and their Latin names. In contrast the list he sent her of the plants growing wild around his home uses the evocative common names but is no less comprehensive for that. The Gravel Garden came into being in 1992, they broke up and enriched the soil as much as possible but also chose plants which would favour the dry conditions and kept careful note of what was thriving.

Letter sent by Derek Jarman to Beth Chatto after their meeting at Dungeness. Jarman described in his diary how after he recognised Beth he ‘almost fell off the Ness’ in surprise. Their visit and this list helped to inform and inspire the Gravel Garden. Jarman had heard of Beth Chatto and was impressed with her knowledge of plants and their Latin names. In contrast the list he sent her of the plants growing wild around his home uses the evocative common names but is no less comprehensive for that. The Gravel Garden came into being in 1992, they broke up and enriched the soil as much as possible but also chose plants which would favour the dry conditions and kept careful note of what was thriving.  Notes made by Beth on the plants in the Gravel Garden after the first two years. What was thriving and what needed to be moved. After the initial planting the garden still needed maintaining: species that weren’t doing well were removed but Beth held true to her initial idea and had the plants pruned back to conserve energy during hot spells rather than water them.

Notes made by Beth on the plants in the Gravel Garden after the first two years. What was thriving and what needed to be moved. After the initial planting the garden still needed maintaining: species that weren’t doing well were removed but Beth held true to her initial idea and had the plants pruned back to conserve energy during hot spells rather than water them.  The Gravel Garden, photographed by David Ward, 1990s. While Beth often took a pragmatic approach to gardening, for example using Round-Up to kill off the grass on the area marked out for the Gravel Garden, she was also aware of the environment and concerned with climate change, writing to friends about her worries for the future. Her ecological approach to planting is in general a more environmentally friendly way of gardening. Placing plants in conditions as close to their native habitats as possible it ensures that they will need less direct intervention and fewer extra resources. Beth was one of the first to realise that planting gardens to suit the conditions was preferable to attempting to change the conditions to suit certain plants. Her ideas spread widely through her writing and lecturing and now it is more common than not to find plant catalogues arranged by habitat. The best ideas often seem like common-sense in hindsight. She was justifiably proud of her own garden but also always pleased to hear how people had used her ideas to create their own gardens, large and small. As she wrote to a young gardening student in 2013: ‘I am delighted to hear you were inspired by my style of planting….I hope you may be helped by my books as I was by my late husband’s research into the ecology of garden plants…I think it takes a lifetime to become a true plantsman and gardener, and then some more! At 90 years old now that is my experience. I hope it will be as richly satisfying for you as it has been to me.’ She always acknowledged the inspiration and advice on planting given to her by her husband and Cedric Morris, but rather than be bound by them she used them as a foundation for her own ideas on ecological planting, culminating in the construction of the Gravel Garden. Her contribution was acknowledged in 2019 when the Society of Garden Design announced an annual ‘a project where the design focus is on the garden’s environmental impact through the creative and ecological use of materials and planting’

The Gravel Garden, photographed by David Ward, 1990s. While Beth often took a pragmatic approach to gardening, for example using Round-Up to kill off the grass on the area marked out for the Gravel Garden, she was also aware of the environment and concerned with climate change, writing to friends about her worries for the future. Her ecological approach to planting is in general a more environmentally friendly way of gardening. Placing plants in conditions as close to their native habitats as possible it ensures that they will need less direct intervention and fewer extra resources. Beth was one of the first to realise that planting gardens to suit the conditions was preferable to attempting to change the conditions to suit certain plants. Her ideas spread widely through her writing and lecturing and now it is more common than not to find plant catalogues arranged by habitat. The best ideas often seem like common-sense in hindsight. She was justifiably proud of her own garden but also always pleased to hear how people had used her ideas to create their own gardens, large and small. As she wrote to a young gardening student in 2013: ‘I am delighted to hear you were inspired by my style of planting….I hope you may be helped by my books as I was by my late husband’s research into the ecology of garden plants…I think it takes a lifetime to become a true plantsman and gardener, and then some more! At 90 years old now that is my experience. I hope it will be as richly satisfying for you as it has been to me.’ She always acknowledged the inspiration and advice on planting given to her by her husband and Cedric Morris, but rather than be bound by them she used them as a foundation for her own ideas on ecological planting, culminating in the construction of the Gravel Garden. Her contribution was acknowledged in 2019 when the Society of Garden Design announced an annual ‘a project where the design focus is on the garden’s environmental impact through the creative and ecological use of materials and planting’  The Gravel Garden around 2009 (c) Steven Wooster Photography All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate unless otherwise stated. An exhibition on Beth Chatto’s ecological planting, containing items from her archive can be seen at the Garden Museum until 21 October 2021. You can find out more about Beth Chatto’s visit to Derek Jarman at Dungeness here

The Gravel Garden around 2009 (c) Steven Wooster Photography All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate unless otherwise stated. An exhibition on Beth Chatto’s ecological planting, containing items from her archive can be seen at the Garden Museum until 21 October 2021. You can find out more about Beth Chatto’s visit to Derek Jarman at Dungeness here