Jane Harrison, Project Archivist: Beth Chatto Archives.

Beth Chatto is known for her writing as well as her garden so when I started looking through her archive I was curious as to what I’d find. I knew there were notebooks of all shapes and sizes but not what was in them or how (and if) the content fitted together.

Notebooks are one of my favourite sorts of documents in an archive collection, they’re most often written with no thought that anyone else might look at them. Even correspondence is written for someone else, if only an audience of one; notebooks on the other hand are only for their writers and as such offer a unique window into how they saw the world and organised their lives. They can be diaries but equally can be workbooks full of practical notes, discussions or observations, and the structure is often just as interesting as the content: meticulously organised or observations scribbled down in whatever direction the book was picked up. Either way they’re a wonderful example of how working with an archive gives an immediacy that no published text can replicate.

The notebooks in the Beth Chatto Archive are written in basic paper memo or exercise books. Some are diaries full of densely written observations on her travels, while others have brief notes throughout or only one or two pages. When I first looked through the second type they seemed not to fit any pattern, most are undated and their content is variable: shopping lists, recipes, lists of plants and occasionally a vivid description of a garden she visited. So why were they kept and how can they be understood?

Looking at gardeners’ notebooks in general you can see how important they have been historically. Starting as a useful tool for the gardeners themselves, they become an invaluable record to pass on to their successors, and eventually a fascinating resource for historical research. With this in mind the Garden Museum asks its Horticultural Trainees to keep notebooks during their placements, which are then accessioned into the archive as a record of how the museum garden has evolved. Even today, when mobile phones are ubiquitous, there are plenty of online articles on how best to keep a written garden notebook. The suggestions are mainly for structured journals for the gardening year but I was interested to see that one of Beth’s good friends, Christopher Lloyd, had a different view. One of his articles from 2004 gives his very specific requirements: ‘A sensible notebook is essential. I keep two of them going concurrently’. These were a diary he took on his travels and a small book ‘… for ongoing notes with names of plants seen or acquired, injunctions to remind me of what wants doing and notes on relevant things seen in other gardens.’ According to his stipulations this notebook must be both weatherproof and able to fit in a pocket or handbag.

This fits the pattern of Beth’s notebooks rather well, both the rough notebooks and the travel diaries. While her little notebooks aren’t weatherproof they certainly show signs of being out in the garden, smudges of dirt and in some cases a light dusting of soil. This idea is also mentioned in passing elsewhere in the archive, where Beth notes that certain friends of hers judge if visitors to their gardens are genuinely interested by whether they ask questions with a notebook in hand.

There are many photographs of Beth in the archive but most of them were taken in her own garden where she is more likely to have a plant in her hand than a notepad. I’ve only found two snaps of her holding one of these little books, both taken on a trip to the Netherlands in August 1993, where she visited Piet Oudolf and made notes on his garden.

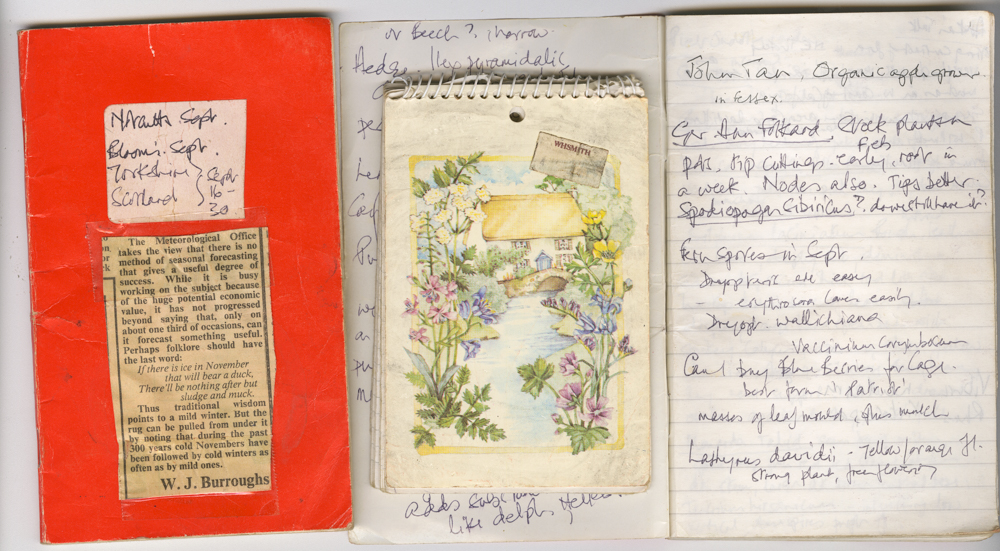

This is a page of that notebook and a good example of her garden notebooks in general, which provide a running account of the sorts of things Beth was doing and what she considered important to remember at the time. This could be a list of Christmas presents, ideas for the garden, dimensions of a possible conservatory or a poetic description of a landscape seen on a journey. In this case, the list of plants she planned to take to Piet Oudolf are just as interesting as the description of his garden and give a record of her visit even without her specifically describing her activities. Note the lack of contextual information: there’s no need to record when and where you are when you’re going to use that information within days. But they’re still so interesting to look through, and invaluable for researchers, they’re full of the sort of daily concerns that you wouldn’t write down for posterity but give such an evocative picture of everyday life.

As a rule Beth bought one size of notebook to carry with her, most often ‘Silvine’ memo books from WHSmith. There are a few exceptions, one being a very small wire bound notebook which she took with her on a trip in October 1983 to Merchants Millpond State Park in North Carolina during her first lecture trip to the USA. This notebook seems to have been written on the move, there’s very little contextual detail but very specific content which dates it to within two days. It consists of lists of plants and animals spotted but also descriptions of the scenery, obviously intended to be added to her main travel diary that evening: ‘utter peace, gliding [through] a forest under water…water so still & clear like black glass the forest is doubled…’.

Beth preferred to sketch the scenes she saw with words rather than draw them; the picture in the image at the top of this article is one of the few exceptions. What sketches there are tend to be practical: visual notes on structures or dimensions, but these can still tell a story. One of the best examples is at the back of one of the mixed notebooks. After several pages of rough notes on gardens visited and a recipe for bran fruit loaf there are a few empty pages then a page with two sinuous lines running down it. The next page has a crossed out scribble but the one after that has a slightly more involved drawing showing a stream with islands within it, it could be quite cryptic if not for Beth’s note at the top: ‘stream banks in Burren suggesting idea for gravel garden with concealed bays and ‘islands’ of plans or boulders or heaps of stones in the middle.’

This image was made on a trip to Ireland in 1991 in the stony karst landscape of the Burren. It shows the beginning of the form that the gravel garden eventually took and is one of the only sketches of its development, as Beth famously used hoses laid on the ground to create her planting outlines rather than drawing plans for them.

The sketch also shows the importance of these seemingly ‘throwaway’ rough notebooks. When discussing her inspiration for the gravel garden in later years Beth would focus on a dry river bed she had seen on a trip to New Zealand with Christopher Lloyd in 1989, but although this far-flung origin makes an excellent story, there’s no evidence from her notebooks that it struck her as interesting at the time, and certainly no sketches. It seems that the plan only properly takes shape two years later, on the trip to Ireland, as can be seen here. We don’t know exactly where Beth was standing to see this, who was with her, or what day it was, but this quickly scribbled impression still gives a sense of the idea forming in her mind, important enough to be jotted down for future reference. Lucky for us that she had a notebook to hand.

All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate.

Notes

The notebooks, and the rest of the Beth Chatto Archive, will be available for researchers to consult once the catalogue has been completed and once the Foyle Study Room reopens. Information on making a research appointment can be found here.

References

Beth Chatto, Beth Chatto’s Gardening Notebook, (London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1989)

Beth Chatto, Drought-resistant planting, lessons from Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden (London: Frances Lincoln, 2000)

Catherine Horwood, Beth Chatto, A Life with Plants, (London: Pimpernel Press, 2019)

Christopher Lloyd, ‘New Years’ Resolutions’, The Guardian, 3 January 2004.