Thirty years ago, on 24th June 1990, Derek Jarman met Beth Chatto on the beach on Dungeness, when she, and Christopher Lloyd, stumbled across Prospect Cottage.

Jarman (1942 – 1994) was one of the most avant-garde film-makers in Britain, the first person to make a film of The Sex Pistols, and was the first public figure in Britain to openly suffer from AIDS. Chatto (1923 – 2018) was twenty years older, a wise and revered horticulturalist, and Queen of the Chelsea Flower Show. And, as Beth’s archive of letters reveal, it was to Jarman – unknown as a gardener – that she turned to for advice as she began to plant her now-iconic gravel garden at Great Elmstead.

Here, Archivist Rosie Vizor tells the story of two very different plantspeople who created thriving gardens in the most unlikely of places.

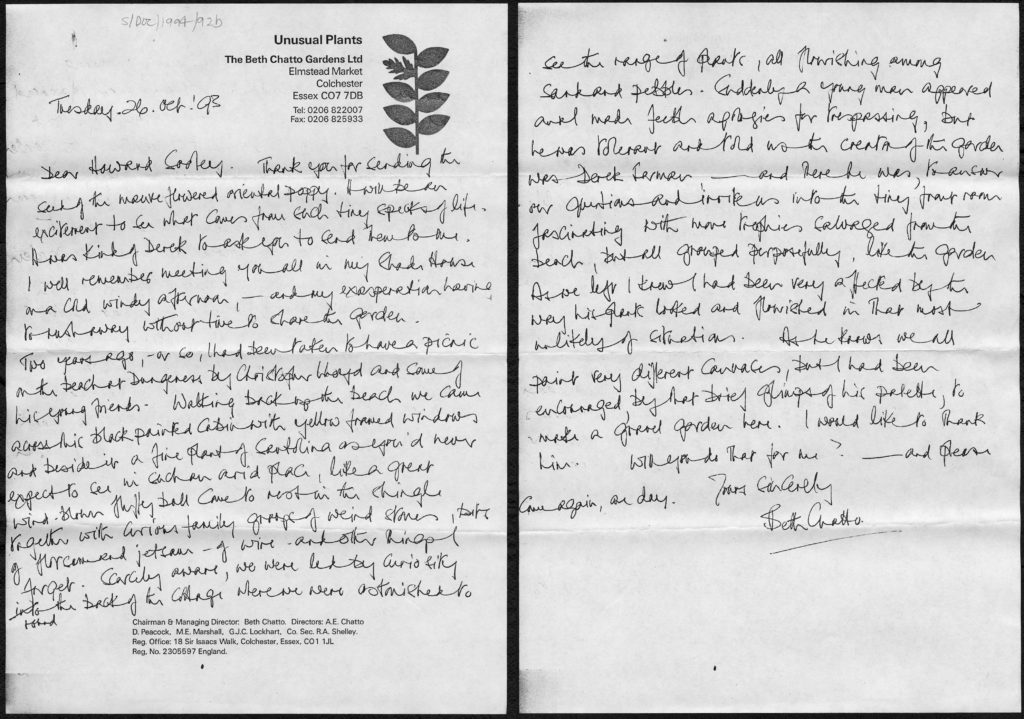

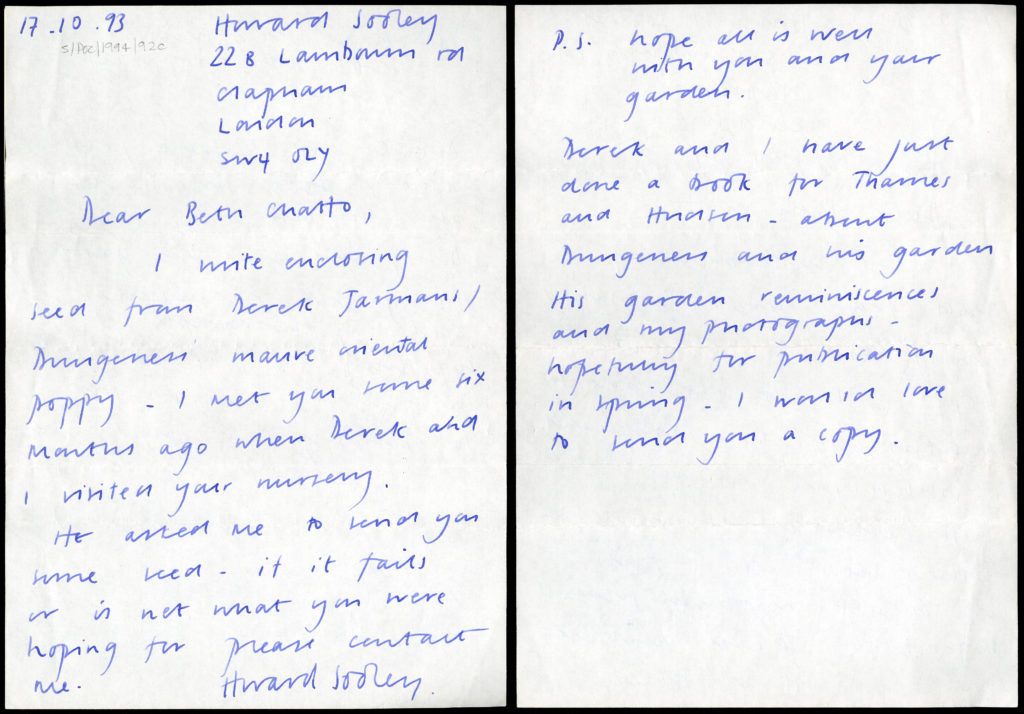

On 24th June 1990, gardening friends Christopher Lloyd and Beth Chatto went for a picnic at Dungeness, a desolate shingle beach on the Kent coast, bordering a nuclear power station. Christopher Lloyd’s reminiscence of this outing is reprinted in the Jarman catalogue but Beth’s memories of this ‘happy day’ can be found in her archive. In a letter to Howard Sooley, photographer and friend of Derek Jarman, Beth describes the moment when, walking up the beach, they came across a Victorian fisherman’s hut painted black with yellow framed windows. Even more unexpectedly, Beth explained, beside the cottage was ‘a fine plant of Santolina as you’d never expect to see in such an arid place, like a great wind-blown fluffy ball come to rest in the shingle together with curious family groups of weird stones, bits of flotsam and jetsam – of wire and other things’.[1] Scarcely aware of what they were doing, Christo and Beth were led by curiosity to the back of the cottage, where they were ‘astonished to see the range of plants, all flourishing among sand and pebbles’.[2]

At this time, Jarman was a bête noire of the British tabloids, an outspoken campaigner for gay rights, and dying… Beth on the other hand, was the daughter of a policeman brought up in rural Suffolk, with what her biographer Catherine Horwood describes as ‘bourgeois instincts’.[3] This was therefore an unlikely friendship but, to Beth’s delight: ‘there he was, to answer our questions and invite us into the tiny front room, fascinating with more trophies salvaged from the beach but all grouped purposefully, like the garden’.[4]

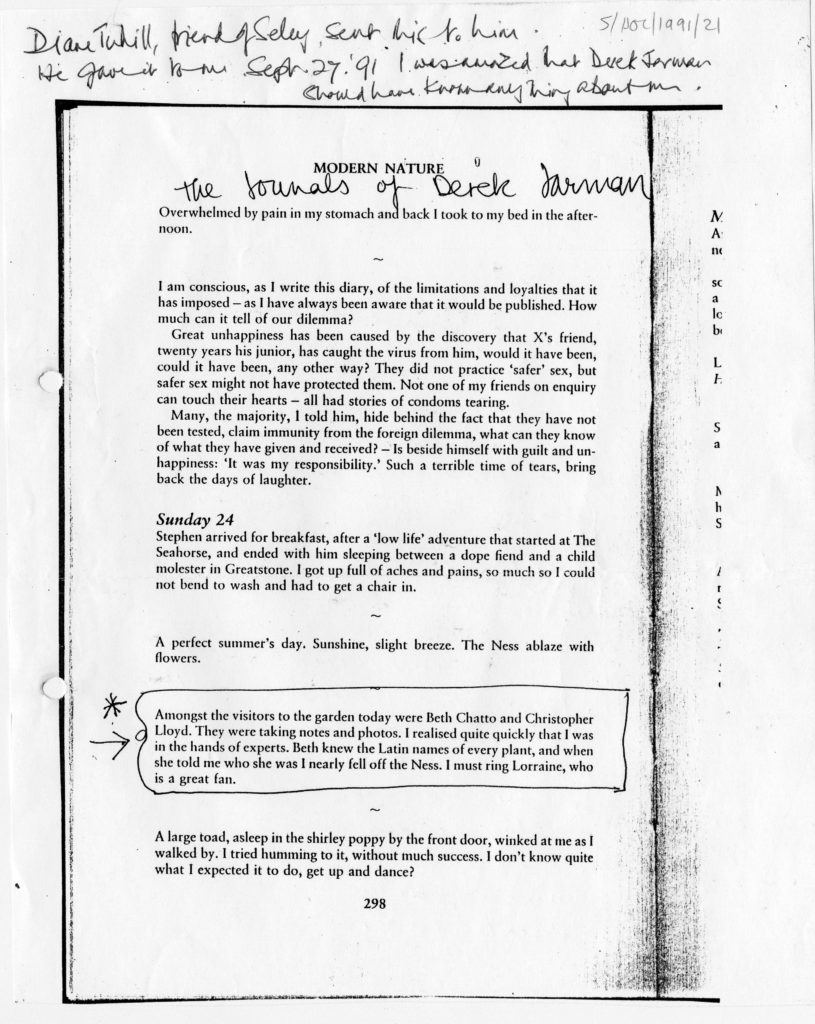

Both parties impressed each other at this impromptu visit. Jarman mentioned Beth in his journal, Modern Nature (1991):

‘Amongst the visitors to the garden today were Beth Chatto and Christopher Lloyd. They were taking notes and photos. I realised quite quickly that I was in the hands of experts. Beth knew the Latin names of every plant, and when she told me who she was I nearly fell off the Ness.’[5]

Beth kept a photocopy of this page in her archive, clearly proud, writing ‘I was amazed that Derek Jarman should have known anything about me.’[6] The visit had a profound affect on her too, as she later explained to Sooley in a letter: ‘As we left I knew I had been very affected by the way his plants looked and flourished in that most unlikely of situations’.[7]

Beth was no stranger to creating a garden in an ‘unlikely situation’. Indeed, that’s what attracted her to Elmstead Market, where she was faced with the challenge of an ‘overgrown wasteland of brambles, parched gravel and boggy ditches’[8], on a slope with varying ecological climates such as dry, damp, woodland and reservoir. Jarman faced a similarly bleak prospect at Dungeness: ‘There is more sunlight here than anywhere in Britain; this and the constant wind turn the shingle into a stony desert where only the toughest grasses take a hold’.[9] After witnessing the success of Jarman’s dry, pebbly garden, Beth wrote: ‘we all paint very different canvases, but I had been encouraged by that brief glimpse of his palette, to make a gravel garden’.[10]

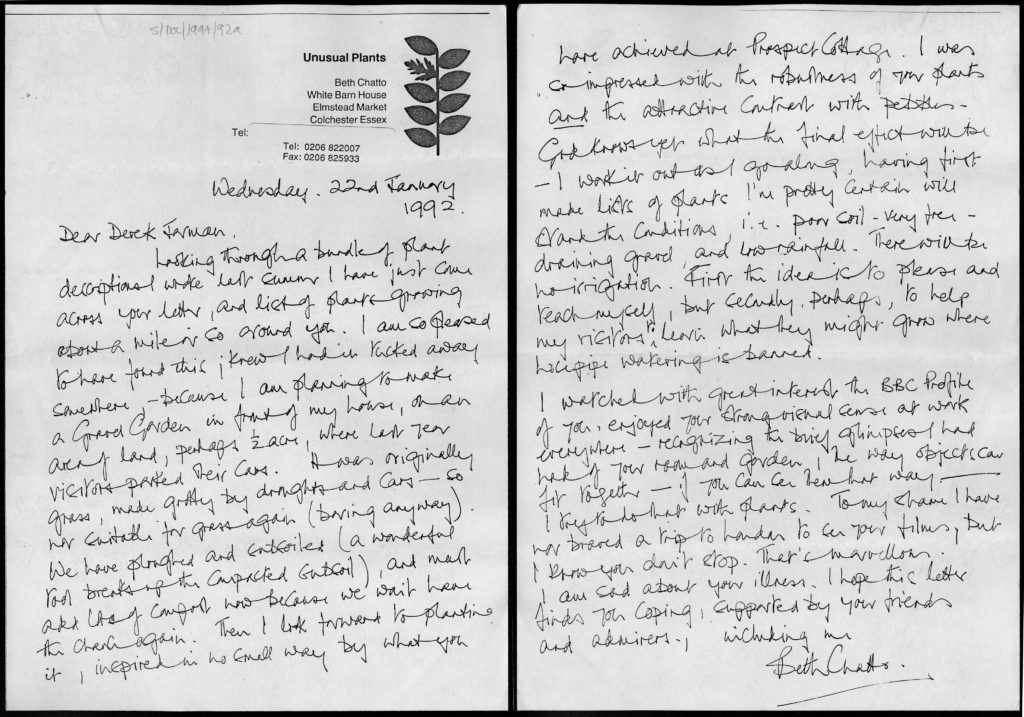

She was thrilled when Jarman sent her a list of plants that he grew. Her letter thanking him reveals the working process behind establishing the gravel garden:

I am so pleased to have found this [list] … because I am planning to make a Gravel Garden in front of my house, on an area of land, perhaps ½ acre, where last year visitors parked their cars. It was originally grass, made grotty by droughts and cars – so not suitable for grass again (boring anyway). We have ploughed and subsoiled (a wonderful tool breaks up the compacted subsoil), and must add lots of compost now because we won’t have the chance again. Then I look forward to planting it, inspired in no small way by what you have achieved at Prospect Cottage. I was so impressed with the robustness of your plants and the attractive contrast with pebbles. God knows yet what the final effect will be – I work it out as I go along, having first made lists of plants I’m pretty certain will stand the conditions, i.e. poor soil – very free-draining gravel, and low rainfall. There will be no irrigation. First the idea is to please and teach myself, but secondly, perhaps, to help my visitors learn what they might grow where hosepipe watering is banned’.[11]

As Catherine Horwood notes in her biography of Beth, it was not just Prospect Cottage that influenced the gravel garden at Elmstead Market: ‘she [also] credited a dried-up river bed she saw in New Zealand during her 1989 round-the-world trip with Christo’ and ‘she later put a sticker on the small red Silvine exercise book she had used for a trip to Ireland with Christo in June 1991 saying, “In this note book I wrote how and where I found the inspiration to make The Gravel Garden”.’[12] This notebook is now in the archive at the Museum with the rest of her papers.

In the last year of his life, Jarman returned Beth’s visit and came to her garden with Howard Sooley, buying plants from the nursery. Afterwards, he sent Beth tiny seeds of a mauve flowered oriental poppy that she’d spotted on the Ness. Although their unlikely friendship may have rested on only a couple of meetings and one interchange of correspondence, the traces of these connections in the archive reveal many similarities between these two gardeners. Most notably, they shared a thirst for creating gardens in challenging conditions and had to think carefully about which plants would thrive where. Beth reveals another similarity in their approaches in a letter to Jarman, when praising his ‘strong visual sense at work everywhere’ in his house and garden, explaining that she tried to do the same fitting together of objects with plants.[13] Finally, they both had a committed work ethic; Beth writes ‘I know you don’t stop. That’s marvellous’.[14] She was saddened by Jarman’s illness, and wrote to him ‘I hope this letter finds you coping, supported by your friends and admirers, including me’.[15]

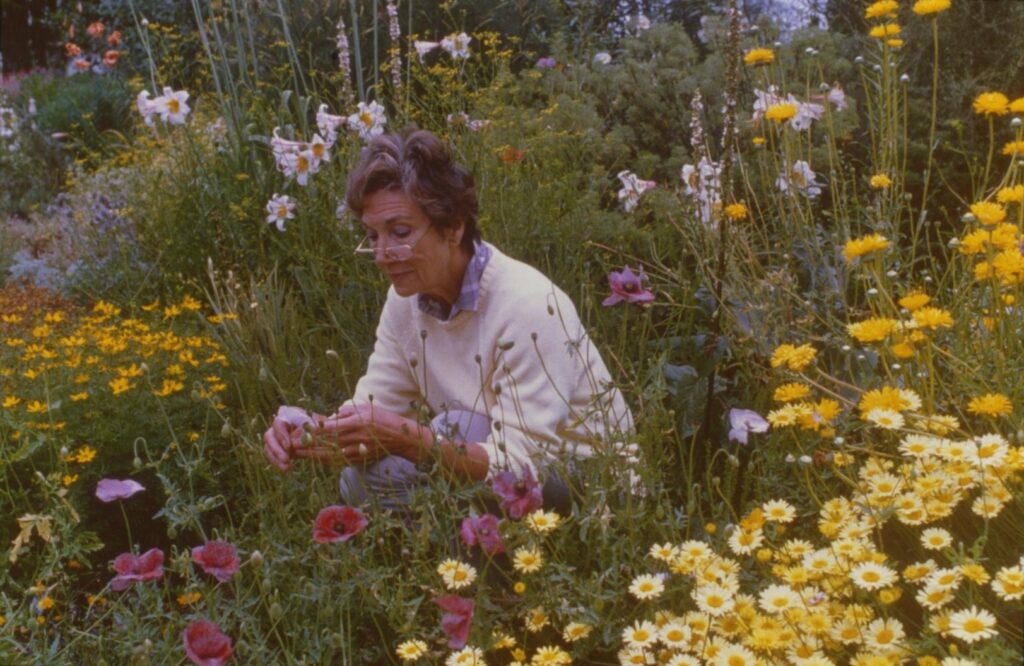

Beth Chatto in her garden (1989) ©Steven Wooster

All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate, unless stated otherwise. Please contact us in the event that you are the owner of the copyright or related rights in any of the material on this website.

Catherine Horwood’s biography of Beth Chatto, Beth Chatto: A life with plants (London: Pimpernel Press, 2019) is available at the Garden Museum Shop, ₤30.

Learn more about Derek Jarman’s garden at our exhibition ‘Derek Jarman: My Garden’s Boundaries are the Horizon’.

—

[1] Beth Chatto, ‘Letter to Howard Sooley’ (26 October 1993).

[2] Chatto, ‘Letter to Howard Sooley’.

[3] Catherine Horwood, Beth Chatto: A Life with Plants (London: Pimpernell Press, 2019), p. 56.

[4] Chatto, ‘Letter to Howard Sooley’.

[5] Derek Jarman, Modern Nature (London: Vintage, 2018), p. 298.

[6] Beth Chatto, ‘Annotated photocopy of page 298 from Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature’

[7] Chatto, ‘Letter to Howard Sooley’.

[8] https://www.bethchatto.co.uk/gardens/about.htm

[9] Jarman, op.cit., 3.

[10] Chatto, ‘Letter to Howard Sooley’.

[11] Beth Chatto, ‘Letter to Derek Jarman’ (22 January 1992).

[12] Horwood, 217.

[13] Chatto, ‘Letter to Derek Jarman’.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.