By Peyton Skipwith, fine art consultant, former Deputy Managing Director of The Fine Art Society, and curator of our new exhibition The Botanical World of Raymond Booth

Raymond Booth was a very shy and private man but despite this he built up an extraordinary network of contacts over the years. Botanists, plant collectors, and nurserymen in Britain, America and Japan were often in receipt of his letters with queries regarding the antecedents of particular species of plants, or information about the explorer-travelers who had discovered them and whose names they bore. He literally liked to get to the root of his subject.

When in his late student days he settled on his lifelong study of plants, he chose for his earliest studies the most boring specimens he could find – the common road-side weed known as Shepherd’s Purse – in order to ensure, in his own eyes at least, that he was not being side-tracked and seduced by the beauty of the blossom before him: he had no ambition to be a latter-day Redouté.

His obsession with accuracy and detail is well illustrated in the works in this exhibition, a number of which show that he gave as much care to roots and corms as he did to blooms. He would not paint a plant he hadn’t cultivated himself through an entire season so that he could observe it in bud, bloom and in decay.

Although I had admired Raymond’s work from the early 1960s, it was only on the retirement of Jack Naimaster later in the decade that I took on the responsibility of looking after and promoting it. Naimaster had exhibited his works at Walker’s Galleries in London’s New Bond Street for some years and when Walker’s closed he brought the contact to The Fine Art Society, where I was already a junior member of staff.

Raymond and I corresponded for several years before I felt bold enough to intrude on his privacy and visit him in the post-war bungalow at Alwoodley on the outskirts of Leeds, which he shared at that time with his parents, and where he continued to live in until his death. After his parents died, he lived alone for a while before marrying Jean – the widow of fellow Leeds artist Ronald Pawson – who worked in the shop from which he bought his artists’ materials. From then on, I was always made welcome by the pair of them and was actually shown work, both finished and in progress, but I never entered into his painting room: Raymond would bring such works as he was prepared to show me into the sunny conservatory, which doubled up as their sitting room.

Not long after Raymond’s death in July 2015 I was summoned by Jean to come and clear the painting room (he never called it a studio). It was a sanctuary, both workroom and laboratory, into which few outsiders were admitted. The only companions he welcomed were spiders, as their webs would trap the flies attracted by the smell of whatever articulated bird or animal – fox, roe deer, badger, or whatever – he was currently studying and painting.

His horticultural models were more benign, though often no less exotic. The prospect of clearance was daunting, as in addition to the somewhat haphazard array of do-it-yourself shelving, and Heath-Robinson-inspired contraptions for articulating bird and animal specimens, there were stumps of trees and other decaying matter carried back from Adel Woods, which had served as props for some of his more complex compositions. It quickly became clear that he had seldom thrown anything away, and Jean wanted everything cleared and, in preparation for my visit, had already ordered a skip.

Luckily my son-in-law, who had at the time his own art moving and storage company, came to help and we quickly filled the skip with the bulkier items, which gave us room to move and begin to clear the shelves, never knowing what treasures we were going to find. We uncovered works ranging from abandoned student exercises to detailed oil on paper studies of field mice, foxes and blue tits, as well as several of the fritillaria studies, the beautiful Iris nicolai, Papaver rhoeas and others included in the Garden Museum’s exhibition.

Over the years these had got buried under accumulating layers of paper and journals so it was a slow and painstaking task. Aesthetic judgments also had to be made – what to keep and what to destroy and consign to the skip. Raymond had told both Jean and I on several occasions that I would one day have to undertake this task.

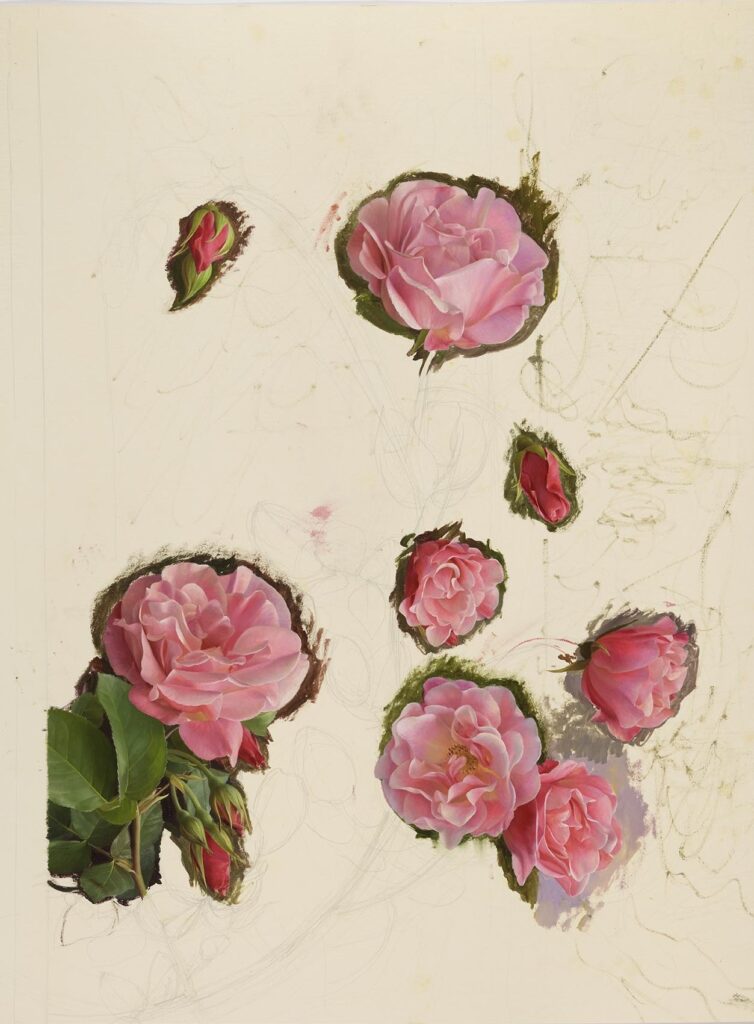

Happily, the division between fully realised works and the failures – those that had been abandoned mid-way for one reason or another – was pretty clear. Raymond himself, if consulted, might have destroyed the sheet of studies of a rose included in the current exhibition as being too scrappy, but to me the succulent, almost tactile, quality of the individual blossoms, buds and leaves made it irresistible.

Apart from his youthful treks through the still largely unbuilt countryside of post-war Britain, when he would spend days and nights living and sleeping in nature, Raymond’s horizons seldom stretched beyond his garden and the nearby Adel Woods, which with their great granite outcrops had proved a source of inspiration to the young Henry Moore several decades previously. This ancient woodland not only supplied him with a ready source of leaf-mould, it provided him with a continually changing microcosm of nature. From his intimacy with its rich flora and fauna he compiled over many years a pictorial Winter Diary, documenting in small intense studies the gradual change from November to early Spring.

His subject matter ranged from fieldfares, those winter migrants recently arrived from Scandinavia, and blue tits sitting on sere autumnal oak twigs, to the brilliant white of snowberries: he lovingly recorded rocks patterned with lichens and moss, the stump of a fallen tree covered in bracket fungi, and willow catkins, those harbingers of Spring, along with unfurling fern-fronds and the early primroses and cowslips. It was an open-ended project never to be completed, but he allowed me to reproduce several pages from it in An Artist’s Garden (Callaway, New York, 2000) and Jean had a few copies privately printed as a labour of love for circulation to close friends.

Adel Woods was to Raymond what Concord, Massachusetts was to Thoreau, and Emerson’s 1863 tribute to the ‘Sage of Concord’ makes a fitting epitaph to this reclusive Yorkshireman, artist and botanist: ‘He ate no flesh, he drank no wine, he never knew the use of tobacco; and though a naturalist, he used neither trap nor gun. He chose, wisely, and no doubt, for himself, to be the bachelor of thought and Nature.’

—