Jean-Marie Toulgouat: ‘The last link with Monet at Giverny’

STORIES

By Patrick Duffy, David Messum Fine Art Upon his death in 2006, Jean-Marie Toulgouat was named ‘the last remaining link with Claude Monet at Giverny’: the place in which he was born, grew up in and died. It was there, in Monet’s old house and studio, among his audacious late canvases, that the young Toulgouat played alongside Monet’s own remarkable art collection, and the famous gardens he had cultivated there for decades.

Monet had been forty-three when he first moved to then small and quiet village of Giverny. Set close to the banks of the Seine, north- west of Paris, location allowed Monet to be able to continue his business affairs in the capital, as well as enjoy the peace of the home and garden he created there. Even before he started painting, Monet set about gardening in order that he had something to paint. Flowers had long been important to the artist, and it has even been reported that Monet remarked towards the end of his life, ‘Perhaps flowers were the reason why I became a painter’.

In 1890 he was offered the chance to purchase the whole estate at Giverny. He did so ‘feeling that he would ‘never again find such an abode and so beautiful a neighbourhood,’ further adding to the property as the years went on. As well as studios for him to paint in, hothouses were constructed for cultivating orchids, and a large pond with a Japanese bridge was built. At this time, Monet’s wealth afforded him the luxury of six gardeners to manage the grounds, whilst he was able to paint some his most well-known series of paintings, including his water lilies series that eventually numbered over two hundred and fifty pictures. The changing gardens inspired in him what he called, in a letter to a friend, ‘instantaneity… in particular, the atmospheric envelope and the same light diffused over everything.’ Monet opened Giverny up to many visitors and dignitaries, among them fellow artists as well as admirers and followers. These included the American painter Theodore Earl Butler who would eventually settle permanently in Giverny, and in 1892 marry Suzanne Hoschedé, the daughter of Monet’s second wife. Their grandson was Jean-Marie Toulgouat. Despite entering a world steeped in art and impressionism, he initially resisting painting, leaving Giverny at the age of 20 to train as an architect. For sixteen years he practiced as a landscape architect in Paris, designing municipal parks and gardens, before returning to painting in 1964. Selling the only original work by Monet he possessed, he returned to Giverny and to the house that he had grown up in, embracing the life of a painter and gardener alongside his wife, the late art historian and writer, Claire Joyes. Together, Jean-Marie and Claire safeguard the integrity of Monet’s last home in an ambitious project that would see Giverny returned to its former brilliance.

Following the sudden death of Michel Monet in 1966, to whom the gardens had been passed, the house and gardens, as well as their contents, were gifted in their entirety to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Without care and attention, the gardens fell into considerable neglect, prompting the Institut de France to engage Gérald Van der Kemp, who had already reinstated the gardens at Versailles, to restore Giverny. The task of planning and reconstructing the long-neglected gardens and studio was immense. Possessing an intimate knowledge of Monet’s home, Toulgouat’s recollections of growing up at Giverny in the 1930s were invaluable for their restoration. It is because of him that ‘the walls in the house were returned to their true colours’. Claire later recalled the sad state of both upon their return: ‘I remember on the second studio’s stairs; we walked on Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters! Viewed from the gate, the garden simply consisted of lawns. There was no structure at all, and the flowerbeds were not planted. The biggest problem? The big water lilies studio where a volleyball net had been installed!’

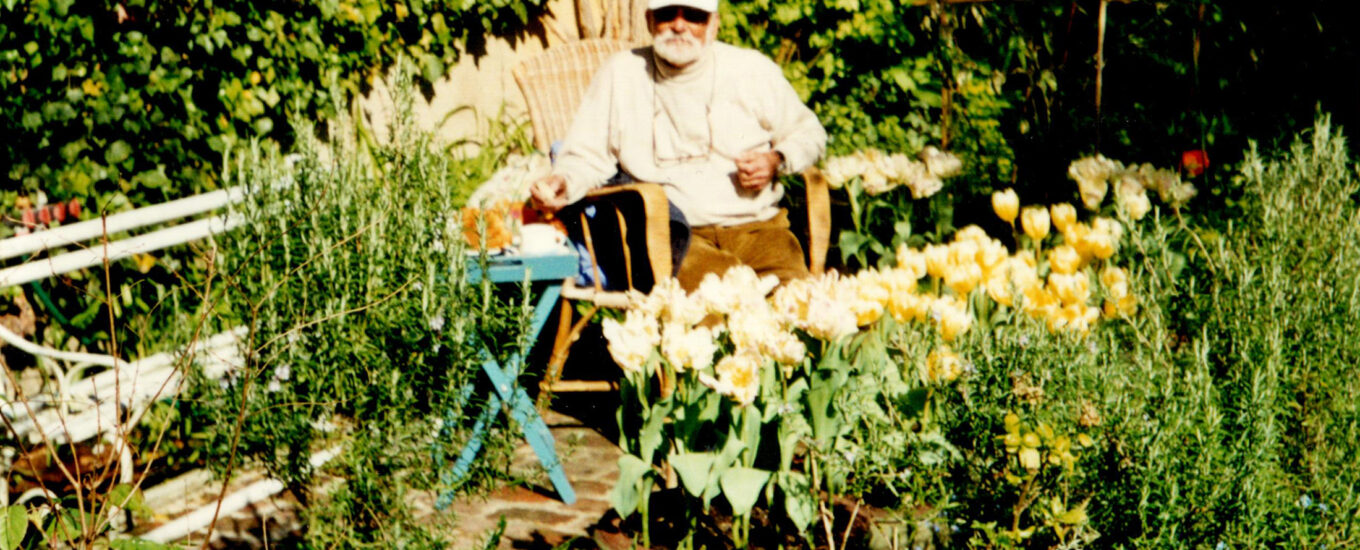

Toulgouat’s architectural training played an integral part in the renovation, mapping out the garden with precision and, with the help of his uncle, James Butler, restoring the original boarders and plantings to Monet’s designs. By 1980, restoration work on the gardens was complete and Monet’s house and studios were opened to the public. Toulgouat and Claire remained at Giverny, painting and writing at their home and tending to their own mature garden which they had created together with its ranks of wild poppies, cosmos, nasturtiums, and touch-me-nots. His link to Monet, though subtle, is clearly in his own distinctive and vividly impressionistic paintings of flowers and gardens which bear witness to his profound connection to French Impressionism, blending tradition with a searingly modern touch.

Whilst the more abstract and linear constructions of the 1960s, bely his training as an architect, focusing on the structure of the enclosed spaces of Giverny, his reflections series of a decade later provide an accent of the palette of the gardens throughout the seasons. These spatially ambiguous canvases depict the dance of colours on the water’s surface reminiscent of those captured in Monet’s famous Water Lilies series. In turn, these works pre-empt his loose and vibrant paintings of the 1980s of the, by then, mature gardens Toulgouat created. The paintings produced in the last decades of his life possess a confirmed spirit of impressionism, but they are more modern in their idiom than Monet’s: a subtle mix of bold and pastel colours in a restricted but carefully selected palette, painted in oils or watercolour directly on to paper.

Giverny has since become synonymous with artist gardens and the impressionists, becoming an important destination for tourists, as well as a surprising stage for international diplomacy. In 1982, whilst on her grand European tour, Toulgouat and Claire played host to the American first lady, Nancy Reagan. Here, in the shelter of the yews and poplars, Toulgouat gave a private tour of the gardens before being photographed demonstrating his own abilities as a painter. On a future visit by Laura Bush in 2008, Claire took up the honorary mantel of steward of the gardens which Toulgouat had passed along to her. Despite the quiet life he enjoyed at Giverny, Toulgouat received considerable recognition in his lifetime, both in France and abroad, appearing in many the major British newspapers. Once described as ‘The High Priest of the Monet Cult’, his and Claire’s commitment to Giverny was absolute, ensuring the survival of the gardens for the pleasure of future generations of artists and art lovers for years to come.

—